Somewhere in between trying to fit in and being stung by conformity, I misplaced my faith in rebellion. The angsty, irrational 17-year old that breathed fire beneath my skin had learnt to let go. It didn’t seem to be worth anything — or so I was led to believe. The indiscriminate aggression that flowed through my veins gave way to what I now choose to call ‘wingback idealism’. A limbless complacence of belief sans the crutches of action. It’s laughable what social conditioning can make out of you. Rebellion never really goes away, though. It’s as natural to one’s constitution as breathing is, going far beyond mere contradiction and aggression. It’s about defining an alternate reality with intensity of thought. Against the times. Against the tide. Against all odds.

Rebellion is not an act but a state of being. Much like the panoramic expanse of a very long motorcycle journey, such as the one I am on, rebellion is seamless transition of accelerated evolution. You’re no longer where you were a moment ago. You’re no longer anywhere. Rebellion is a journey by itself. It takes you places. The idea of rebellion is not to oppose but to create, and creation, as you and I know it, is endless. You’re no longer in the now, even. You just have to keep going ahead. A gear down and the Royal Enfield Himalayan is roaring towards a confluence so wild, I’m afraid for my life. They said it was impossible. That’s what they always say. Rebellion is as fundamental as a fresh change of underwear. Everything else is makeshift, at best.

The Himalayan, right from when we set out, was not only a choice of motorcycle but the reason of rebellion. A motorcycle built for the Himalayan landscape, the Himalayan was a bold, if incomplete, statement of the changing times. The Himalayan is a motorcycle for the mountains but also, more importantly, of the mountains. It’s a motorcycle that was built around the prayer flag — the ubiquitous accessory of the year that has just blurred past. It lent substance to the growing spirit of motorcycling adventures. Its rebellion, however, was in going as far away from home as was possible. Away from the forgiving isolation of third-gear terrain. Away from a land that makes conquests out of mere attempts, conquerors out of survivors. Out here, at the edge of land, it had to fight for nothing but its own redemption. I decided to bring my own battles along for company.

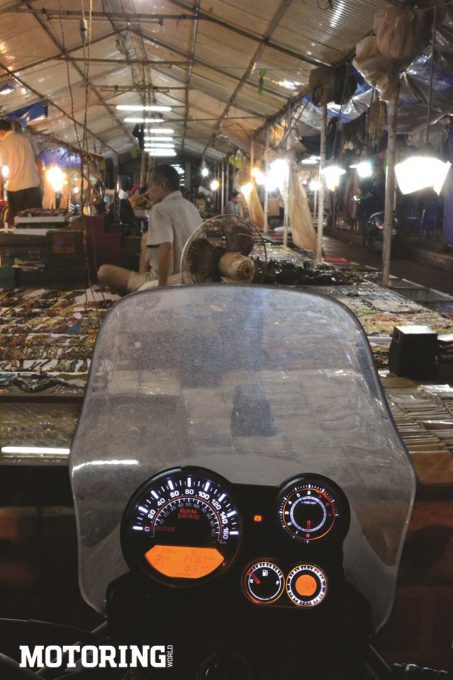

Only a few days earlier, life wasn’t as intense. We’d parked ourselves in a congested lane in North Goa, comfortably detached from the dreadful chaos of revelry. Rain had threatened to bring my ride from Mumbai to Goa earlier in the day to a halt, but we’d made it somehow. It wasn’t the most eventful of motorcycle trips I’ve made so far, but the fear of not making it made the completion seem important enough. I’d hung my rain-soaked riding gear out to dry and, having changed into a tee and a pair of denims, half-face lid in tow (I carried two helmets along, but more on that later) and a magnetic tank bag to lug around a basic and very battered Nikon, I set out for an evening of soaking it in.

Goa, on the map of rebellion, is the first step. All forms of rebellion are essentially journeys. Goa, in that scheme of things, is nascent escapism. Running away from where you thought you belonged. Or thinking you’ve run away from where you belong. It doesn’t matter what you think of Goa. It thinks nothing of you. You are like the waves that crash on its shores, unfailingly, ceaselessly. Nothing here is permanent. Nothing ever lasts. Particularly not the fake Ray-Bans you feel the itch to buy only when you’re in Goa.

Behind its pastel walls have lived generations who themselves don’t belong. It’s one large vegetarian-restaurant-infested caravan of gypsies. It’s an escape — not wholesome enough as rebellion itself, but a beginning, nevertheless. Escapism, contradictory to popular belief, isn’t an act of cowardice. It’s a sort of prep school for the conscience before you get to bigger things. By giving into escapism, you open up to judgement. It’s the first sign of shedding inhibitions. I cracked open a can of Red Bull, the Himalayan parked on its centre stand, me perched comfortably on it, and sat idly as travellers around me made their way to whatever lent their existence a sense of purpose. Everyone’s out there, trying to look rich; self-appointed representatives of the good life, all. A fine young gentleman threw up all over a potted plant to my right.

It’s okay. Revelry is no crime, for sure. So much for wearing crisp white linen trousers, though. The next few days, I idled away. I’d set out on my motorcycle, camera in tow, with not a plan on the cloudy horizon. Friends like good old Delbert Fernandes — the man is living, breathing proof of all that is right with this world — extended their hospitality over endless rounds of fried calamari and particularly relishing crab. I made a few new acquaintances, too, all impressively motivated in their own conquests — some feeble, some with waterfront mansions to show for it. The escapism in me had thawed. It was time to move on.

Escapism is not difficult. Letting go of it is. With the one-piece tailbag neatly strapped on, I was now truly on my own. The Himalayan seemed unaffected by the monumental course that lay ahead. Maybe it was all in my head. Maybe they put it into my head in the first place. The next 600 kilometres were crucial because there was no home along the way. The lashing rain, just like the unfamiliarity, helped nothing. The Himalayan’s long-stroke single-cylinder motor thumped reassuringly — quite the irony, since it’s the very lack of assurance that brought about its rebellion to begin with. It made me feel like we’d make it just fine. To make promises is one thing, however. To see them to the end is quite something else.

I carry a half-face lid with me when I can because, on motorcycle journeys, I like the role reversal of primary and peripheral vision. The reversal isn’t perhaps one in the most technical sense or I’d have wound up splattered onto the back of a truck, but a larger bubble visor extends your peripheral vision substantially. It’s less limiting and enhances the feel of travel. From the perspective of a motorcycling purist, a half-face lid is more fatiguing and, without a doubt, less secure as well. But I’m not against the clock in any way. I just have to make my escape seem worth it. I need to see more, feel more. My rebellion will remain incomplete without it. Mine, not the Himalayan’s.

The road from Panaji city in Goa to Dharwad in Karnataka is one of the best motorcycling roads in the country. It’s not so much the mostly-impeccable tarmac nor the scenic wilderness (especially towards the tail end of monsoon), but the sheer scale of aloneness you experience while traversing through the foggy hills and dense forests. There’s not a soul in sight for kilometres on end and it takes motorcycling commitment to an altitude like little else can. The feeling of being watched never leaves me for even a moment.

Speed took care of everything that day. One stop for chai, over the course of which I underwent an unforgettable tutorial on how to man a British-era railway crossing, one stop for fuel and that was about it. I hadn’t intended for a particularly intense day of riding, but that’s more or less how it turned out to be anyway. I didn’t mind as long as the motorcycle didn’t. They had their doubts about the Himalayan being able to cope with the highway. It wasn’t fast enough, some had said. It wouldn’t last, said the others. The Himalayan was having none of it. Neither was I. It was one of those days when not riding with a certain intensity would prove dangerous. The escape had cleared out the cobwebs, at the very least.

Bengaluru was my only chance, the last of the lot, to decide if the rebellion was really worth giving it my all. Turmoil at the border that separates Karnataka from Tamil Nadu seemed to cloud my opinion. There was little heroism in venturing into troubled waters, pun intended, especially when reports of indiscriminate immolation and gay abandonment of law and order were rife. To be turned to ashes, buried under 182 kg of molten Royal Enfield metal wasn’t exactly part of the plan. Kartik had joined in at this point, having driven all by himself from Mumbai. Together, we’d figure it out, like we had always done in the past. Rebellion is individualistic in its outlook, but impossible without a collective, regardless of its righteousness or the lack of it. It was time for redemption.

Rameswaram was a sunny day away and we scattered ourselves down the fast wide-open four-lane motorway. The speeds remained constantly in the triple-digit region and, towards the trailing end of the morning, it began to get reasonably warm. The border we’d so dreaded had turned into a fortress, with armed defence personnel keeping the tension off the streets. It was hard to ignore the swarm of local travellers walking, children and bags in tow, over to the other side for over a kilometre since public transport movement had been restricted for fear of being targeted. I’ll have to admit it was unnerving, but not more than it was peculiar. I was overdressed for my immediate environment, too visibly detached from it all. This was their battle, not mine. Humanity is a flimsy pretext, sometimes.

As the sun dipped below the horizon, we made it to Rameswaram on the coast of Tamil Nadu, the last trace of civilisation if not life itself, on the other side of which lay the fulfilment of our rebellion. The illusion of it, at least. I’d only read about this believably quaint coastal town so far and, through the yellowed pages of the few travelogues that sit atop my bookshelf, it seemed to have not much to offer apart from a bit of peace, worship and quiet. Rameswaram, unlike its mirrored coastal counterpart — Goa — however, doesn’t enjoy a ‘tourist season’ that spans a few months. The season here lasts a day. Just one full day. The one day we’d decided to arrive.

We were unceremoniously shown the door from our hotel, which we had booked weeks in advance. The proprietor broke into a fine act of being a shrewd businessman and being unable to comprehend any language known to mankind. Not fair, but what choice did we have anyway? As it turned out, he’d not only chucked us out of our perfectly legitimately spoken-for room, he’d also chucked us out of the last room available in all of Rameswaram. I was furious. Kartik was less so, but then he’s always one to reason. An air-conditioned pigeonhole we found later was our redemption for the night. It was better than the undoing of everything, at least, although I didn’t think of it this way at the time.

My hate for Rameswaram had seethed in comfortably by the time we hit the sack. I was liberally venomous in what I wished upon the packed-to-the-gills town and indecently vocal about it, too. That the bathroom door had a rather grim representation of oceanic life in the form of a pair of happy dolphins on the surface, with two menacing sharks lurking beneath the surface didn’t seem to cheer any of us up, either. There was morbidity to the humour in our short-lived conversation that night.

It would be very unfair not to make this confession, since it is something that has played on my mind all along the ride — I was very afraid of making it here. I never wanted to get to Rameswaram and Dhanushkodi, where we were that day. For all my inexplicable love of the ocean and everything it brings to the shore, I hate being vulnerable to it. Rameswaram posed the first of the roadblocks — well, not really — with its 4-km-long Pamban bridge. I’d been dreading getting here days before I’d even left home and when we finally did, I more or less flew atop it. As if that would help in any way were the bridge to go down. But, to my mind, the sooner I got done with it, the lesser prone I was to its fallible (in the scheme of eventuality, at the very least) structure. I don’t know if Kartik noticed my restlessness through the windscreen he was behind. I hope he didn’t.

The ghost town of Dhanushkodi was no better. My fear of the abandoned strip of tarmac-layered sandbank came from the very reason it was declared a ghost town in the first place — an incomprehensibly rapid rise in the sea level, caused by a cyclone in the December of 1964. It must have been horrid, to say the least, considering roughly 1800 people were swept away in the devastating fury of nature. The raging Indian Ocean on one side, a serene Bay of Bengal on the other, Dhanushkodi is surreal in a way that belittles ordinary imagination. The scale of it is one thing, but it’s the visual dimension of it that weighs you down. You see Earth — well, the watery bits of it anyway — like you never can elsewhere. It does appear to be round, honestly.

Fear, much like anger, is a fascinating emotion. To be an observer of the effect it has on the human psyche — or my own, in this case — is simply spectacular. I’m afraid of a lot of things, all of which revolve around death. I like immortality. I don’t want to die. Immortality may be a metaphor the meaning of which I might uncover over the course of life, but for now I choose to call it just that. I like being alive. Being alive is fascinating. I hate living in fear. I hate flying, as much as I’m besotted with aviation. I hate snakes, too. I hate things I cannot fight. It’s not the inability to fight due to weakness, but due to powerlessness, not being in control. It’s not healthy, but it’s like this anyway. We’re in Dhanushkodi now and the final strip of 6-km-long tarmac — the symbolic completion of this rebellion — is out of bounds.

It’s a freshly laid-down tarmac straight, awaiting inauguration at the hands of the now-deceased chief minister of Tamil Nadu — may her soul rest in peace. Police officials flag me down. I try my hand at reasoning, but the fear I’m fighting within turns it into an argument which I lose. I’ve given up. Eight days and 1700 km later, this is what my fear has brought me to. A non-existent stop sign planted in my mind by people I’ve met five minutes ago, which I’ve succumbed to. Fear is ridiculous. Kartik decides to give it a go. It works. I can’t say I’m too happy. But the admission of fear is only a little bit bitter than the experience of it. He hops on as pillion. We have the road ahead all to ourselves. We’re the only two breathing organisms on the most hauntingly isolated piece of road in India. Well, at least one of us is breathing. I’m holding on to the Himalayan’s handlebar tight, trying to focus on the thrum of its exhaust note. To be on a motorcycle makes me feel less vulnerable, less susceptible to mortality.

The Himalayan is poised as ever. It can’t possibly know where it is, but I like to believe otherwise. There is a romance to associating a psychology to machines, which is why we’ve come such a long way. Eighteen years of writing about the personalities that dwell within sweeping sheet metal and aerodynamic fairings can’t not affect the way you think, the way you are. The Himalayan has faced flak for not being a lot of things it should or could have been, according to them. They are right, too, on most counts. Right now, however, there is nothing but the sound of silence. No one’s here to see how far the Himalayan’s made it. No one’s here to extend it a round of congratulations. That’s how it always is. This is why rebellion is important. It’s not an action. It’s symbolic.

A roundabout marks land’s end down the last bit of tarmac, beyond which lies the confluence. No matter how far you go, you always come around. The completion of life is in itself a confluence. Ashes to ashes, atom to atom. It’s not about turning back but about completion. The circle is symbolic of the highest order of completion. On its own, the circle is of the least value — like the number 0, for instance — but it is the definition of everything. Life without it wouldn’t be life at all. It would be merely experiential, not creational. It’s creation that begins — and brings justice to — everything, rebellion included. Creation is eternal, singularly unique in its every quality. You cannot confuse creation with anything. It’s what started it all. Against time. Against tides. Against all odds.

I still flew back down the Pamban bridge on the return leg. The Himalayan made it home the way it had left. Any other motorcycle could have done it, but the Himalayan did it. Its rebellion stands completed, though nothing has changed since. Maybe it was all in my head, after all. All of it, for nothing. Or was it?

I’d like to thank Delbert Fernandes and Karan Lokhande, without whom this journey would have been incomplete.

[This story was originally published in our January 2017 issue]