I simply couldn’t get cars to go where I wanted them to. Having gently ‘nudged’ an elderly gent on his early morning milk run, rather permanently beached an SUV on a dune, and attempted to dent a stationary rock using a German hatchback, it would seem I was pretty determined to bringing my motoring journalism career to a crunching and rather premature end. I thought my time was certainly up when I attempted, unsuccessfully, to mow down a tree, right outside my editor’s home, using — you guessed it — a car. It didn’t matter that he bore no visible attachment to said tree.

The redemption, if any, was that all of these ‘experiments’ happened on separate occasions. Each time, I was given a thorough dressing down but, more importantly, a chance. Eventually, it worked. I can now get cars to go where I want them to. Not just into a pond, for instance, but out of one too. Thankfully, I was not such a handful with motorcycles. Save for a lowside on a 150cc bike and a highside, also on a 150cc bike (oh, well!), my motorcycling graph looked visibly more aesthetic than the one involving two extra wheels. I see why many, including those with even a fleeting interest in physics, would find that strange.

In the years that followed, I spent a lot of time riding and writing about motorcycles. It entailed many, many thousands of kilometres of discovering things about machines, the country we live in, and about myself. Then, I decided I had to get a ‘real job’. Being here began to feel inadequate. It was no longer enough.

Wild, Wild Country

The Thar ploughed through the slushy trail without too much effort. It was real sticky, the sort that can make a good 4×4 gearbox sweat a fair bit, but momentum, a load of low-end torque and very little driver intervention saw it find its way forward. I couldn’t see much through the flat windscreen; the rain had come down properly hard, threatening to drill through the hardtop. This part of north Karnataka was infamous for its ‘stray’ wildlife and, at the time, the thought of negotiating myself out of being devoured by a member of the big cat family seemed too tedious. We’d been on the road for roughly twelve hours. Sometimes, doing very little, but being absolutely observant, is all you need to do to emerge from a difficult situation. It’s not an intuitive thought, but it seems to be an effective one.

In the austere comfort of a wood-panelled rainforest cottage, Disha (my monumentally better half) and I arranged our belongings, unpacking only the essentials. We had (somewhat unequally) decided to make an elaborate stopover in the dense forests of Yellapur, before taking the coastal road leading to Goa. While she decided on a nap, I helped myself to a coffee and sprawled out on the porch. For a view, I had towering trees and a Thar that was still being pounded by the rain. In the distance, a small but powerful stream could be faintly heard over the din of the relentless rain. A tungsten tinge enveloped the scene as light faded, and a few moments later, it turned completely dark. The rain only grew more ferocious. Fearsome.

A dinner of chicken curry, hot rotis, and a vegetable preparation provided a welcome distraction from the relentless downpour. I asked for a coffee afterwards, and Disha decided to ask for one for herself, too. The conversation as we sipped from our mugs wasn’t particularly remarkable and bordered on plainly evident observations, something that made us feel a sense of belonging in what was truly wild, wild country.

I lay awake in bed long after Disha had fallen asleep. My mind was in a complete state of awareness.

An Illusion

Soon after I had left Motoring, for another stint in motoring journalism, I found myself belted up in economy class long-haul flights around the world a lot more. The motorcycles continued to arrive home, although now with some sense of officiousness, and my face had begun to be plastered all over a tiny slot of weekend television (for which I can never apologise enough). Week after week, boxes would magically appear on my doorstep, sent across for the purpose of experiencing their contents and, sometimes, with the expectation of a ‘review’ of some sort.

It began to feel as if my opinion mattered. My perspective or simply view of things had somehow become a thing of importance, of seemingly real value, to others. A dwindling GDP would see many become unemployed, ill and homeless, but it didn’t keep them from excitedly absorbing the nuances of the Skyhook suspension you could have on the Ducati Multistrada 1200S.

On social media, where I had become a sort of sensation (even though with a miniscule footprint), I assumed the responsibility of creating the opportunity for questions to be asked, so that everyone could consume my answers to them. Not answers, you must note, but my answers. While this concept lacked originality, borrowed as it was from the dozen odd of my ilk who had already indulged in such practices, it took nothing away from the sense of reward. In due course, I became familiar with a handful of people’s urges to have a photograph taken alongside me, a phenomenon that continues to haunt me to this day. As a small mercy, it helps me tremendously that most people never seem to be able to remember my name, or at least aren’t sure at first, because then I can introduce myself like a conventional human being and save myself the long disappointment of looking at a person trying to figure out exactly why you look familiar to them. On each of these agonising occasions, I miss writing for Motoring. Motoring people never ask for their photographs to be taken alongside you. They know. It’s always the stories. That’s what it will always be about. People who read this magazine have lives to lead rather than follow.

Trust And Humanity

Rear-wheel drive is a beautiful thing. At the base of a towering dune on the outskirts of Jodhpur, I remember being instructed in a clear, almost sing-song manner about building momentum in ‘4- High’ and then maintaining steady revs all the way to the top. I didn’t believe Naresh Bhosle at the time and something about the underconfident look in my eyes made him point out a Mahindra Marshall steadily making its way up the very dune. ‘That’s a two-wheel drive,’ he said, ‘so you can easily do it.’ I was in a Bolero Invader, Mahindra’s last attempt at a short-wheelbase 4×4 until the first-generation Thar, and seeing as there was no point in a philosophical discussion with Mr Bhosle at the time, I did as advised.

Ploughing through the dense Yellapur foliage at a comfortable clip in third gear, I relived that moment from a decade ago. Sometimes, the front wheels would drift animatedly off course and, on others, the rear wheels would spin-up owing to a heavier than necessary pre-emptive throttle input, but the Thar would compose itself and keep us pointing upwards. Rear-wheel drive is almost always enough. It had taken me years to make the distinction between the abilities of a 4×4 gearbox and the inherent capabilities of a vehicle. The technology would always be an assistant, an enabler, but never a substitute for a vehicle’s natural state of being. The Thar was in its element, laying down its fat spread of torque comfortably. Machines rarely make mistakes. It’s always the people.

Jayanth anna knew this trail better than anyone else. He frequents it on anything he can lay his hands on. His presence in the co-driver’s seat was of comfort, not simply for his knowledge, but also because he has a real ‘man of the woods’ air to him. His giant frame and sizeable mane makes him appear easily distinguishable in an urbane setting but out here, amidst nothingness, he exudes a relaxing confidence that comes from instinct and experience. In each year that we have met since the first time I visited seven years ago, I relearn the process of trusting every word he says, reducing the unlearning that ensues as I bid farewell and head towards ‘civilisation.’ He’s simply not the kind of man to get you into trouble. But he’ll always take you close to it. From where he sees it, it isn’t close enough anyway. I guess it comes from having abandoned the urban landscape years ago, to raise an entire family as proficient in domestic affairs as it is in the department of riding dirt bikes. It’s a most absurd unit, that family, their gentle faces and gentler demeanour hugely belying their individual strengths.

Later that evening, they showered Disha with presents and warmth of the sort she’s never experienced anywhere outside of her own home, insisting most determinedly that we stay on another evening in their company. It was a heavier goodbye than we had anticipated and, over the stormy four-hour drive to Goa late into the night, we would speak about the depths of their humanity and affection in great detail.

Memories in Mapusa

One morning, I woke up in a palace hotel in Jodhpur, in a room the erstwhile King used for some purpose or the other. It was an expensive room — the price of a night’s stay could buy you a small car — but beyond that, I remember nothing about it. Not the colour of the walls, not the style of television (or whether it even had one) or the name of the woman whose portrait hung on the bedside wall. Rather, if there even was such a portrait in the first place. Sixteen days on the road, in what must have appeared on the social media feed as an orgy of the ostentatious, and yet in reality, none of us had the luxury of being present. A long time after the trip had ended, I began to realise how entirely on its head my concept of awareness had been turned. By some stroke of luck, that it had begun to feel unnatural hadn’t escaped me. Soon, it progressed to feeling unreal. And then, violent.

Disillusionment is often only an accident, but it’s when you begin to live by it that it can really get you into great danger.

I woke up at five-thirty. Through the skylight, I could tell daybreak was a comfortable while away and I set about tip-toeing through our AirBnB cottage, getting clothed for a few hours out by myself. A moment later, with barely a sliver of the sky turning a deep blue, I fired up the Thar and reversed carefully out of the driveway. We had a week in Goa ahead of us and, as is the case on each of our holidays (invariably in Goa, much to the recent distaste of my wife), I would wake up at an unearthly hour and return only very close to noon. This seems to have become an agreeable arrangement between us, even on a regular Sunday back home, as I hold dearly my reputation of being a morning person while my wife, given the opportunity, enjoys her sleep most enthusiastically.

The diesel engine in the Thar, among its nicest features, in my opinion, had so far comfortably established itself as an amply willing cruising accomplice. I don’t care much for its seriously high refinement levels — long after I am gone, I wish to be remembered as someone with the distinct ability to find a deep romance in a grieving Greaves Lombardini motor — but its tractability and just its energy is something that lends a lot of real good to the Thar’s personality. In the highest acceptable gear, with a very light foot on the accelerator, the Thar glides rather casually — the equivalent of wearing a loose floral shirt to the beach on a windy day. It’s the kind of state of mind that matches the frequency of the air in Goa, and their pairing seemed to have a monumentally calming effect on my being.

The sun still hadn’t risen by the time I was in Mapusa, or Mapuçá, the latter being the more aesthetic and culturally appropriate rendition of the name. The municipal market in Mapuçá has long been one of my favourite places in the state, especially for its overpoweringly strong fragrances— from the flowers, spices, meats and fish — which can guide you most effortlessly through all of its many compartments. This early in the morning, however, is almost exclusively the domain of what is, for me, the market’s centrepiece — the bread wallahs. On a dedicated podium reserved for them, the bread stalls are few in number — three, I think — with the deck opposite entirely leased by a couple of young ladies who specialise in traditional Goan sweets, but arrive only later in the morning. It’s the bread that forms the epicentre of the market and, in fact, of most traditional meals. Bread, as far as available knowledge can be trusted, is not native to India, having been introduced in its most recognisable form by the Portuguese. The ‘pao’ constitutes many a breakfast or evening snack across the country, although what brought me here was my love for poee — the round, hollow form of bread which, in addition to pairing well with absolutely any imaginable food item, makes for a great snack by itself. I asked for a dozen or so to be packed, and the vendor (a nice guy; he never minds my cameraphone taking a few liberties with his produce) shuffled through one of his few large baskets, wrapping the stash in the previous day’s newspaper. I picked one off the lot, stepped off the podium, and casually strolled over to the crummy and shapeless tea stall right behind the bread station. I’m not a habitual tea drinker or anything, but something about that moment or setting warranted draining a quick cup of hot chai. Having handed out the due sums of small change to either vendor, I resumed my walk through the market, now reshapened as an entirely aimless exercise.

I believe my expectation of most such expeditions on foot is that they must lead to some sort of psychotropic escapade or at least a newsworthy crime scene. On most days, though, I find satisfaction in my ability to just be present, or to make clear and detailed observations, something that has been an inability of mine and a subject I will continue in the following chapter.

Things of Substance

I began experimenting with awareness at a young age. Stillness, silence and being were assumed by my vocabulary and consciousness towards the tail-end of my teens. Unsurprisingly, it created a noticeable degree of conflict — quite the contrary effect to what I had expected. A moment of absolute silence has tremendous depth, entirely sufficient to envelope your existence. Absolute silence is most natural and needs no intervention. It is not repressive, like what monks endorse, or in any way a byproduct of discipline. It is, in fact, the most liberatingly indisciplined form of being. From absolute silence emerges an enormity of mindfulness. Known in an active form as meditation, mindfulness is a heightened sense of awareness, of every microsecond of life. In very simple words, it is the state — not the action, mind you — of being completely present.

The idea, once you have absorbed it, takes over and begins to bloom in the most beautiful way. You could be in a war zone, in the middle of a most ferocious stampede, and yet find silence and calm and energy and fulfilment in it. This is the reason behind the popularity of drug consumption across the world — because drugs have a way to chemically alter biological affairs in order to replicate this experience. Drugs, however, can only offer a momentary ascension. Heightened awareness is a manner of being, not an anatomical anomaly. A drug is a capable stimulant but ultimately only a facsimile of the real thing — of life, and being so utterly enveloped by it.

In the seedy bylanes of Arambol, with its deeply embedded Russian-Ukrainian settlements, it is already evident how drug usage has been reduced to colourlessness. A mere psychedelic attraction, like those horrible temporary tattoos, or fish pedicures, in other parts of the state.

Dream Sequence

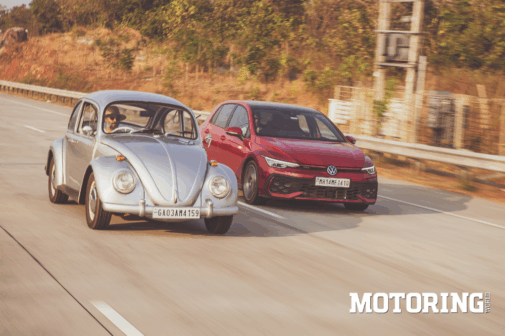

There was always ample opportunity for Motoring to become anything. Mostly dead, that is. Had it been created, or sustained for that matter, for any of the wrong reasons available, it would have long disappeared off news stands. When it was a thirty-buck magazine, the founding editor put a pair of 300-kph motorcycle missiles on the cover. By the time the cover price rose to fifty, supercars were a consistent fixture below the masthead. You wanted a cartoon-animation cover — heck, an entire story designed that way? Motoring gave it to us before we could have imagined it. A silhouette of a madly-in-love couple flinging their arms around each other against a setting sun and a Porsche Boxster? Here’s where it happened. They even flew in an Anglo-French photographer for that story, I remember.

I spent my most fundamental years being a part of Motoring. Rather — and it would be more accurate to say this — being a part of Motoring is what made those years so fundamental. It isn’t momentary, this belonging. Once you’re in, you’re always a part of it — even if you try hard not to be. I know I really, really lucked out, having been given the chance.

It’s a simple little rag, made by people who can dream, and be driven by those dreams, better than any other bunch of people you’ll ever meet. Often, it so easily gives the impression of being hallucinogenic; it’s always been a young team convinced about chasing the most vivid of ideas, with a belief system that is uncomfortably indifferent. Of course, it wouldn’t be that way without the people who made it and the people who eventually ensured it remained so against every imaginable odd. Thankfully, and in deep gratitude, I can say that about myself, too.

PHOTOS Disha Anand