‘My grandmother once told me a story,’ went Harsh Man Rai, my companion for the ride, on the first day’s stop. ‘In Nepali folklore, there’s a kind of witch called boksi. And there’s only one way to escape her — run downhill.’ Why downhill?’ I asked, setting myself up perfectly for the punchline. ‘Because her breasts sag till the ankles and she trips on them running downhill!’ Even in the peals of laughter that ensued, I knew that I’d forever recall this story every time I was going downhill, be it a ghat or a flyover. And there were a lot of downhill stretches on the Konkan coast, so I found myself shouting, ‘Boksi can’t catch us!’ in my helmet very often. However, there were also an equal number of uphill sections. They were completed in wary silence.

Witches aside, the most important part of this ride were fairies… um, ferries. Seven ferries in total all the way down to the promised land, sticking as much as possible to the infinite sea that meets over and over at all points on the planet. We were riding from Mumbai to Goa for Royal Enfield’s Rider Mania, but there was a difference. We’d planned to take the longest possible route there instead of bombing down NH48 in a day. The point was to turn a ride that’s usually a matter of hours into one of days, and see where that took us. As it turned out, this approach spread the senses in all directions, both physically and temporally, and that little story was but one result of said expansion. We spoke about many things, but we’d always circle back to life, time, words and wonder. And as far as photographs went, I wanted to come back with nothing but photos of motorcycle, sea and sky. On that count, the trip was a resounding success. On other counts, even more so.

I: Making Good Time: Mumbai to Harihareshwar

The first was a roll-on/roll-off or ro-ro vessel from Ferry Wharf in Mumbai, a really big and well-appointed one operated by M2M Ferries. It neatly deposited us onto the mainland, right at the point where the interesting part of the road began, eliminating the transport section between Mumbai and Alibag. From some time after Mandwa, it seemed like we were on just another regular commute; speed breakers and errant vehicles made it seem like we hadn’t left Mumbai at all. But as we got closer to Kashid and Murud, conditions became a lot more agreeable. And before long, the road became one tailor-made for motorcycles, and we rode like a coven of boksis was hot on our tails.

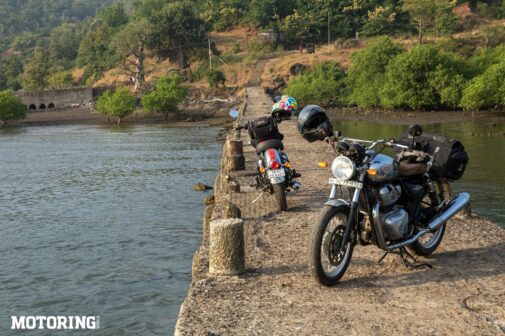

Ever since the Classic 350 came home, I’d wanted to do this very ride on it, and the motorcycle did not disappoint. With no pillion seat marring the beautiful rear mudguard’s lines, I had to deploy a tank bag for luggage and it also ended up being a good ‘front rest’ for my bulging torso. And halfway through the day, I was convinced that a Classic café racer was in everyone’s best interests. And since Harsh’s Interceptor and the Classic had to ride in an overlapping range of speed between 60-80 kph on open roads, we ended up setting personal efficiency records as well. How about 28 kpl for the 650 and 36 kpl for the 350? And yet, a certain disquiet had started to settle in my mind.

It was unsettling to be going anywhere, not somewhere. We didn’t have a set destination for each day, and every ‘Where should we stop?’ was met with a shrug and a ‘Let’s see where we reach.’ And there was a ferry for every shrug issued. The second one was from Agardanda to Dighi, and we spent the entire ride looking at the map and wondering where we’d get to. And as I looked at the placid water, it struck me that hurrying to a destination, to safety, just might be an act of ingratitude. In fact, all wishes are inherently opposed to gratitude. We spend too much time with the former when the latter is all we’ll ever need. And then I saw that I already had everything I needed, on that ferry and in life. Was it a lack of conventional ambition? Was it peace? Is the absence of one required for the other to take root? We rode along the sea, not getting a single drop of water on ourselves. We weren’t making good time, but beating it altogether.

II: Making Time Stop: Harihareshwar to Ganpatipule

On the second morning, we hopped out of bed and sat in front of the bikes drinking tea as they warmed up. The sound of their combined idling seemed to surround us and not go very far, even though it was a cool and quiet morning in Harihareshwar. By now, I had unwound, let go of the destination, and was ready to settle into the ride’s rhythm. It was going to be just another lazy, comfortable and fun day, just like the previous one. Nope. It was full of gravel roads — but is it gravel if it makes alarming noises against the motorcycle’s unprotected underside? If there were a word I’d ascribe to that surface, it’d be ‘rubble.’ Somewhere along the road in a forested patch, a langur ran across the road and then ran right back. The playfulness of that fellow primate jolted me out of the greenery-induced trance that’d come over me.

Meanwhile, Harsh was right at home in those conditions. He’s a man of the mountains, after all, and has spent considerable time riding in the Himalayas, so a bit of Konkani off-roading was no big deal. In any case, the Classic’s aftermarket comfort seat worked wonders along with the fat wheels to make the ride as easy on my back as possible. And that let me look around more than I normally would. The coast is repetitive in its beauty, but never boring, just like riding a motorcycle. Putting a motorcycle along a coast, then, meshed them in a manner that vapourised time entirely.

Riding next to the sea was always quite the feeling. And when the road led away from the shore, the Konkani hills entertained us with corners of all shapes and sizes, and we could only oblige. The day seemed to pass slower for our benefit, and we only aimed ourselves at the next ferry. The first one of the day was from Bagmandla to Vesavi, the second from Dabhol to Dhopave, and the third from Tavsal to Jaigad. And each of those fortified a thought that came to mind on the first one — will we ever know what’s under all that water? Even what lies in an estuary? Think of it on a planetary scale and it won’t be long before you wonder if those waves are welcoming or warning us. For reference, more than 80 per cent of the planet’s water remains unexplored.

III: Wibbly Wobbly Timey Wimey: Ganpatipule to Mithbav Tarkarli

The day began with an immediate case of helmet-mind. In this state, the rider just wants to keep going, photos be damned. We passed one lovely spot after another but didn’t stop. The bike had taken over and it wouldn’t stop. We saw beaches of all kinds, from powdery white to hardened black sand and everything in between. We also met more traffic since Ratnagiri was on the way, but thanks to the smooth blacktop, before we knew it we were already 45 km into a 130-km day. And so we wrestled ourselves to a stop on an isolated beach opposite Devgad Fort for a not-needed breather.

It was a lovely beach, one that could hold its own against any in the world, like all the sandy strips we’d seen until then. It had trees, falling at the front line of the shore like a first wave of soldiers against an irresistible opponent, the sea. But that’s not what made it remarkable, it was the garbage inside the treeline. Konkan is littered with breathtaking spots. Unfortunately, almost all of them are littered by the discarded remnants of human life as well. I am a fool and a coward, for all the things I don’t understand and all the things I’m afraid to face. And I bet this extends to the rest of my species as well. How long until we finally feel the pain of the blue sea? The angst of the air we breathe? The shivering of the soil we stand on? All of these things that give us life?

We have too many beautiful places, too much history, and too many people to mess it all up. I believe that people are good everywhere, far from evil. But should ignorance be classified as malice if it results in hostility to the environment? We saw people filling sand from the beaches in sacks, trucks waiting to carry them away. Beaches turned into dumping grounds. From one of the ferries, we saw cows on a beach eating plastic bags instead of the seaside pasture it could’ve been. When I saw such things, it was easy to accept that Nature can’t be cruel enough in return for what we do to her. Then I looked at the Classic’s chrome perfectly reflecting the water and the sky. What an irony that the result of such a toxic process looks best in nature. Beauty and pollution, the paradox that makes up human existence. Never mind, the motorcycle will always give you the right feelings you need.

We missed our planned stop at the Mithbav MTDC because it looked like it was abandoned; the road up was pristine, but the forest had started taking over it and the gate was firmly closed and rusted. We rode on, then, and by the time we reached Tarlkarli, an evening sunset had taken over the beach. Fishing boats arrived, men digging the sea with oars. I wondered out loud if those guys think of their boats like we think of our motorcycles, and got no answer in return. The process of parking the boat and offloading the fish was an elaborate one that required extensive team work. The word ‘community’ gets thrown around a lot these day, but there it was in real-life action as a real-world way of life. Meanwhile, a bunch of dogs ran along the beach digging holes, and then running from one hole to another, just being the happiest creatures that ever existed.

IV: Making Time Count: Tarkarli to Vagator

The morning began with watching more fishing boats and more dogs. We began the last day of the ride with the same semi-reluctance that takes over when you know a good thing is going to end, even if another good thing awaits where we reach. It was a cold morning and we rode at a gentle pace, always promising ourselves we’d stop after 30 minutes. The terrain showed us yet more forested slopes that led up to grassy plateaus and then twisties swooping down into valleys. The road rose and fell, like the waves we’d been watching since the ride began.

The Classic climbed up one slope after another even in its higher gears, the percussive beat of its exhaust deeply mocking gravity, as the Classic suddenly felt like a determined and dignified locomotive. State transport buses seemed to be racing in a private championship that no one else knew about. The sight of one of those red monsters filling a helmet visor was a scary one and those drivers seemed to know it, too. And after a couple of hours, we realised we’d already entered Goa — we’d missed the last two ferries. The first one because there now stands a bridge over that creek, the second because a well-meaning gent we asked for directions sent us over the final bridge into Goa, and just like that we were at our favourite watering hole in Vagator for breakfast. It had taken us less than three hours. Sigh. An elongated ride had come to an abrupt conclusion. Endless days had terminated in an instant.

V: Time’s End: Nowhere to Everywhere

We remembered the sights of the ride: Locals trying to race us on 100cc bikes; two bulls locking horns in the middle of the road; a Force Traveller coming around a right hander with a bright pink ‘Drift King’ sticker on its nose. All those stories will continue even if ferries don’t. We live in stories, our real ones, and then the ones we tell ourselves and each other. That makes all stories interconnected even if they don’t seem to be so at first glance, and they’re the fundamental atoms that make up our lives and relationships.

If not, I don’t see how a 61-year-old ‘millennial’ and a 39-year-old ‘boomer’ could ride together over four days. In fact, on the second day, I noticed his lines through corners and commented, ‘I saw that you’re taking more or less the lines that I do. Either we’re both riding well or we’re making the same mistakes!’ The road was mostly terrible, often heavenly, and never boring. In fact, I don’t remember the bad roads, only the spectacular beauty of the Konkan coast. You might think that water looks the same everywhere, and maybe it does, but it’s your perception of it that shifts. As with a motorcycle, with proper maintenance, thoughts go as far as you need them to.

I realised I was made for movement. Besides moving physically on bikes, that is, and that made it even better, somehow. I couldn’t have asked for better company, both two-wheeled and human, watching what water does from a ferry, on a beach or from a cliff. On a motorcycle, escaping the inevitable end is a daily exercise. This ride was a beautiful extension of that, one more attempt to understand the beings that are motorcycles which have this hold on me. As do life and time and words and wonder. I hope to welcome every motorcycle, every place, every thought as a friend. And keep them in my life even if disagreements arise from time to time. Isn’t that what ferry tales are all about?