Bombay is like a pug. Both are mostly unsightly and always out of breath. Hence, without any formal call for it, I appointed the pug as this city’s spirit animal a long time ago. As I stood pointing my KTM 390 Adventure’s Austrian-origami face at the Gothic edifice that was once called Victoria Terminus, and noted the empty space under the clock where her statue once stood, I remembered that Queen Victoria herself was quite obsessed with pugs and had several for company. ‘What a coincidence,’ I thought, mulling over the connection between this city, a queen, and a dog breed of Chinese origin for whom was coined the Latin phrase ‘multum in parvo’ or ‘much in little space’. They might as well have been talking about Bombay. Except for today.

Two months ago, an invisible enemy brought the city to a standstill, its residents compelled to batten down their hatches and mask their faces. In some cases, people had to leave the city but that was easier said than done when a lockdown was sprung and modes of transport shut down. For all intents and purposes, it felt like a trap to the 20 million or so people that call this reclaimed set of islands home in one way or another. After two months of being indoors, I rode straight into the first rain of the season. The showers helpfully noised up a city that was eerily empty, haunted by the absence of its people. In 37 years, I don’t remember seeing anything like it. Police barricades marked off containment zones everywhere I went.

Bombay is a small part of our beautiful country. Every country on the planet glorifies its cartographical shape and thinks it’s the greatest; right now, there’s someone in Tajikistan going, ‘Damn right, we’re the best.’ In this context, Mumbai is just another crowded mess, with inordinate attention showered on it because the Portuguese and British deemed it so a very long time ago. But even before the Europeans came squabbling along, kingdoms rose and fell here. Bombay is a lot of things, always has been. Especially a prime candidate to produce a superbug that’ll make COVID-19 look like the common cold.

It used to be seven different islands. It’s been inhabited for at least 2000 years. Ashoka the Great once ruled over it, but the longest reign was the Shilahara dynasty’s 543-year slog. Between and after the two, several kingdoms, sultanates and vassalages rose and fell until the Portuguese came along. A Portuguese man called Garcia da Orta was awarded a lifelong lease to ‘ilha da vida boa’ or ‘island of good life’, and he was the first colonial resident of Bombay. Later, the city also had to suffer the indignity of being dowry between the Portuguese and the British. In its existence, it’s been called by over 20 different names. And if I were born 12 years later, I imagine I’d call it Mumbai like anyone else.

If Bombay were a motorcycle, it’d be a really tall two-stroke, waiting to catch you out. This noisy city’s vertical character enveloped by a permanent cloud of smoke may have led to that image. That rainy morning, though, was one of the rare days on which the roads were empty. Earlier at CST, the junction it faces was not seen that empty since people first started photographing turbans, dhotis and bullock carts in front of it in 1887. The KTM spun its rear tyre, traction control turned off, through the streets of old Bombay, its tall presence imitating the buildings around it only in altitude, not beauty. Even the Art Deco buildings tut-tutted at the bike’s gawky insectlike appearance, forgetting that they hid slums behind themselves. As the rain fell, I wondered if the monsoon would bring its regular flooding hell along with it.

Bombay’s narrow existence is riddled with narrower streets and alleys. On one side, it gives people the magnificence of Marine Drive. A little to the east, it hides its docks from prying eyes. And in the middle are buildings crammed together in an almighty game of architectural Tetris. Even the photos you take of this city are best in a vertical frame. From the north, modern glass-and-concrete monstrosities continue their slow swagger towards the defiant stone-and-brick heart of the city. I spent the first 30 years of my life in PIN 400001, and it doesn’t get more Bombay than that. But I had no access to a camera for most of that time, and consequently I have nothing to hold and gaze fondly at except foggy memories which mostly asked the question, ‘That building wasn’t there, was it?’ I held back a sneeze, lest anyone hear.

The Bombay I grew up in is the stuff of middle-class legends. Black-and-yellow Fiats and red BEST buses to be dodged on a daily basis. An elderly Muslim taxi driver who wrote the most eyeopening poetry. A middle-aged office-goer on a Shogun who raced my college-going Pulsar 180. The inevitably-named Tony who ran a superbike workshop a short walk from home. Finding places across the city to hide from the world… well, mostly parents and other nosy adults. A place often frequented was the Queen’s Necklace; the crowd provided anonymity for broke teenagers smoking away their meagre allowances. Later, the same place allowed sea-side drinking for equally broke college kids, an eye out for self-righteous cops. It was the best view in the world, although nostalgia has since erased the smells.

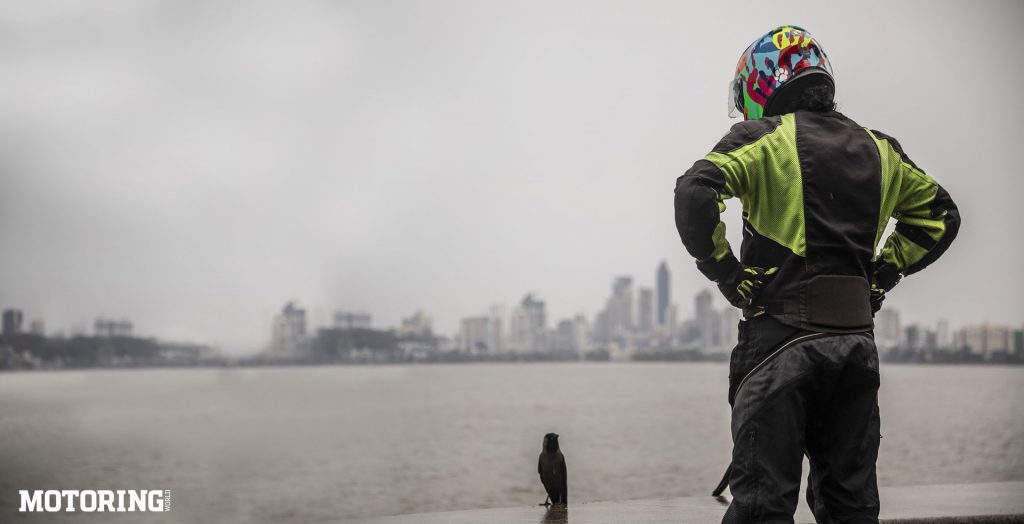

Ready friends were to be found everywhere in the countless stray dogs that shared Bombay with me. And I betrayed them all by getting a pair of kittens home. The descendants of those dogs, as vigilant as ever, turned up when the KTM and I reached Marine Drive. I imagined they could smell my guilt. Yet another establishing shot of Bombay, Marine Drive wore a vacant look that is normally found on the faces of government clerks. I thought about all the people who come here in movies, resolving to one day make their mark on the city. I wish I was there to tell them that the city doesn’t care.

Movie theatres, with their dark-chambered escapism, are microcosms of this city. To get away from this place, people go deeper down the cinematic rabbit hole. Perhaps the first thing that Bombay brings to mind is Bollywood, its unimaginative name a herald for what it spews at the world. The city wears its movie theatres as jewels, some precious, some fake. They’re landmarks, proof of Bombay’s faith in make-believe, along with places of religious worship. Theatres are generally more inclusive, though. Even capitalism and communism watch the same movies on the same screen. Or at least they did until they put the screen high up in multiplexes.

My very first memory of the city is not of a specific address, but a moving location — a motorcycle’s tank. I remember the wind in the face and the sight of movie theatres, Marine Drive, VT and similarly magnificent buildings. Stinging embers fell from my dad’s cigarette onto the back of my neck. If I reacted, I’d get a whack and was told to be a man. Strange thing to say to a boy, I used to think. In any case, it left me with the flinching ability of a stone, leading many to speculate that I suffered from some sort of nerve damage. They were probably right. Years later, Bombay’s roads became the anvil on which my riding was shaped, the knocks all too literal on occasion. And each time, I looked up at the indifferent city, picked up the bike, and moved on.

Why are people drawn to this city? The times, over hundreds of years, have changed. The reasons remain the same. Call it a better life. Call it trade. Call it commerce’s uncle, greed. Half of the people in Bombay today are migrants. The other half came from migrants. Everyone comes here attracted by the hope this city offers. But they also come here to escape from something. They accept this city’s danger and routine heartlessness in exchange for the lessons it brands them with. Whether it’s the sweat of the poor or the fat of the rich, the policeman’s stick whacks them all equally, while the middle class forms the water in the great grinding mill that is Bombay. And they all become the city as it absorbs them.

If this city had a motto, it’d be, ‘Everyone wants to be like me. Tough luck.’ Bombay has reached far beyond where it began, both in location and consequence. It was always a global city, steeped in its own inherent madness. I don’t know if that matters to the people sleeping on the footpath outside the Bombay Stock Exchange. My friends and I used to race down these roads, a circuit we designed for maximum mayhem. Raging hormones and internal combustion mix rather violently, as you can imagine. And yet, the KTM and I coasted along at half throttle; I just don’t feel like making a mark on this city anymore, both metaphorically and literally. Despite being born here and having the city infused into my being, the years have stripped away its sheen. But it doesn’t matter that I don’t call it home as I used to, the city still claims me as one of its own.

Perhaps I’ve indulged in a futile resistance against a city that’s seen me fail repeatedly, and yet has been a shoulder when I needed it. A shoulder that shook with laughter but was warm nonetheless. I wish I could say that to the migrants who sat outside VT as I rode past, but I don’t know if it’d be of much help. They weren’t born here, and their problems are beyond any futile philosophy I can provide. I can only wonder if they will be back to this city, now that they’ve seen its unforgiving face. And if, when Bombay starts breathing again, it will ever be the same.

[This story originally appeared in the June 2020 issue of Motoring World]