The essence of a café racer can be distilled into four simple words — look good, go fast. I believe it’s this clarity of thought that allows this breed of motorcycles to attain that sensuous and universal purity of form and function. What began 1950s’ Britain as a reckless activity to the tune of 45-rpm records playing on Wurlitzer jukeboxes has today turned into a fundamental expression of the motorcycle. And here we have three coffee machines that span across time — the 1958 BSA Gold Star DBD34 from the birth-era of cafe racers; the Triumph Thruxton 1200 R which is the ultimate modern-day production café racer; and the Royal Enfield Continental GT 650 which is India’s latest and greatest contribution to this evocative sub-culture of motorcycling.

Gazing at these three under a dim early-morning winter sun, it’s easy to understand why motorcyclists have happily struggled with caffeine addiction of the mechanical kind for roughly 70 years. The continuing design brief seems to have been, ‘Add purpose. And a round headlamp,’ and that’s it. Oh, and, ‘Make the rider sit in a position bordering on the indecent.’ All three motorcycles find their aforementioned purpose and racy riding triangles delivered via clip-on ’bars and rear-set ’pegs. All three will test your patience in traffic and reward you when roads have more curves than Beyonce. And yes, all three will break past the tonne on their respective speedometers, some more easily than others. And, despite belonging to different eras of engineering and economic considerations, all three translate that same essence of café racing into mechanical reality. Let’s start at the beginning.

The Gold Star is a legend (a fine example of an understatement). And it became one through a thorough domination of the Isle of Man and British roads between transport cafés. It was a working-class hero — an idea at the very heart of café racing — and it remains one of the most popular motorcycles of all time. The DBD34 was the ultimate Gold Star you could ride out of a showroom back in the day, and this particular one is a fine specimen, five-gallon tank and all. The right amount of polished alloys glinted at me mixed with the right amount of black. It’s so simple; stubby clip-ons, basic fenders, basic suspension, a sweptback exhaust, a couple of meters, and some fins under that beauty of a tank. And yet, I just knew I was looking at something special. Standing next to the Thruxton, that’s saying something.

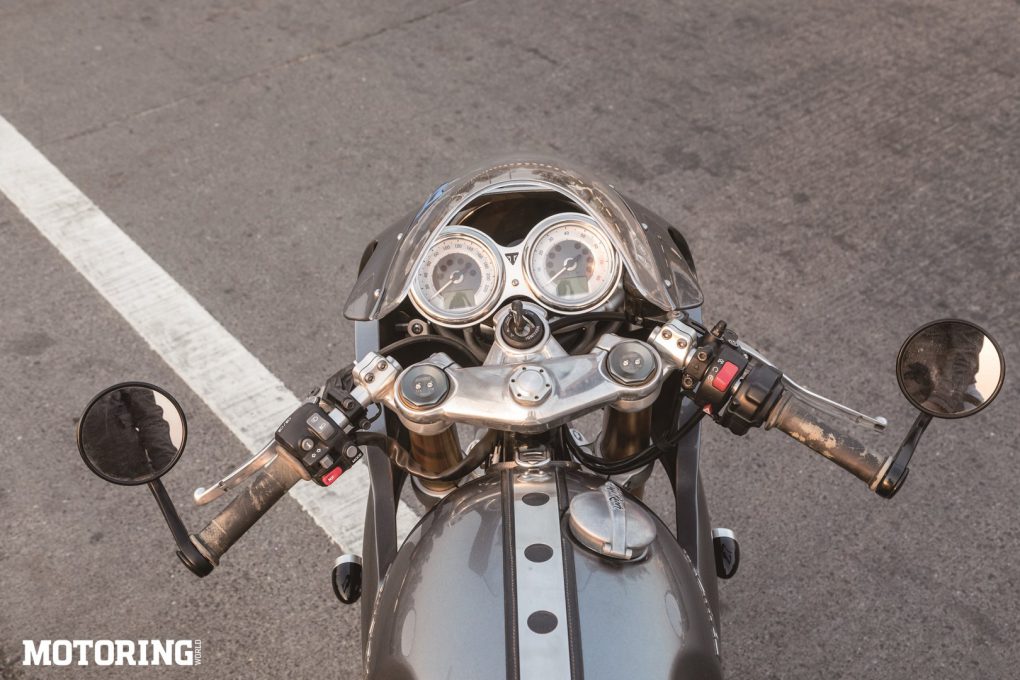

Part of the Gold Star’s decline during the early 1960s was the advent of the Triumph twins, and that lineage is represented here by the Thruxton. It’s one of the most gorgeous examples of retro designs coming together with modern engineering, and it knocks me out each time I see it. It has all the right details, be it the tank strap, the golden upside-down fork or the carburettor-impersonating throttle bodies. And every surface sports a finish that declares mankind’s mastery over production techniques. It’s one of my all-time favourites, and I expect it’s the same to thousands more. Which brings us to the Continental GT 650.

If you’re wondering why Royal Enfield persists with the Continental GT name despite the previous 535’s failure in India, it’s because a 250cc single carrying the same name earned the company a huge following back in the ’60s and went on to become one of café racing’s most iconic motorcycles. And late last year, after the old 250 and the short-lived 535, the badge got the motor it deserves. Finally, the Continental GT can again roll into this early-morning burn-up with its head held high. Until it’s caught daydreaming and passed by the Gold Star.

You see, the Goldie might be an oldie, but its internal-combustion fires still burn for speed. Kicking the 500cc aircooled motor awake, I was surprised to note that it sounds exactly like a Bullet with a loud exhaust, only a lot more free-revving. This particular model features an RRT2 close-ratio gearbox, so I assumed that it’d be quick shifts up and down the 4-speed ’box. However, engineers of the 1950s seemed to have thought a close-ratio gearbox should have second, third and fourth gears reasonably spaced out — and a first gear that’s good for 100 kph. Yes, you read that right. So, the overall feeling as you get going, slipping the clutch (and half-giggling at mental slipper-clutch jokes) to engage fully, is that the Gold Star has four gears — first, the tall fourth, and then three shorter fourths.

This long-legged nature is the dominant feeling in the Gold Star’s riding experience along with that quintessential British-single thump. I didn’t feel like I was going all that fast once I short-shifted to fourth fourth gear, but I was already past 100 kph. The Gold Star was barely past tickover at that point and there was three-quarters of the throttle left to turn, so I have no doubt that it used to be good for 180 kph back in the day. I gave it the stick a couple of times, and it gathered speed in a blur of single-cylinder vibrations. That motor does a lot more than its 42 bhp would suggest.

And the few sweeping curves I came across, the 170-kg Gold Star roared through them in a manner that clearly illustrated why it was the choice of road racers of the past. The whole idea is to build speed with that gearing that’s taller than the Eiffel Tower, and then hang on to that speed using the frame’s stability and nimbleness. Braking, as expected, was a mix of tears and prayers, right next to useless, so I don’t know what those past racers did to slow down. Makes me thankful for modern cycle parts, that does, and brings me back to the Triumph.

The Thruxton might come from the land where café racing was born and from a company that played a huge part in fostering that culture, but it feels decidedly Japanese after riding the Gold Star. There is a slickness prevalent in everything it does — without feeling clinically sterile — right from its 1200cc motor to its top-notch cycle parts, that makes it so much fun to ride fast. It offers 96 bhp and weighs 203 kg, and a whole lot of finesse. And speed. A lot of speed. The Thruxton will run away from pretty much anything on the road except perhaps the most determined superbikes, and even then I have my doubts. It brakes and turns like a sportsbike, but has that beautiful feel of a parallel twin, and that makes for a fulfilling riding experience. And as those close to me will attest, I miss no opportunity to fixate on the Thruxton, so please let’s move on to the Continental GT 650.

With 47 bhp and 198 kg, the Royal Enfield presents horsepower closer to the Gold Star’s output with a weight closer to the Thruxton’s, so it’s understandable if a first-timer squints at it with curious derision. But I’d ridden it before and knew exactly what it’s capable of. On a tight and twisty road, not even the Thruxton could get away from it. In fact, the 650cc motor is so familiar in feel because its smooth and pleasant manners are approximately exactly like the Triumph twins. I suppose that’s what you get when you hire most of Triumph’s designing and product-planning teams.

Long story short, the Continental GT 650 does everything that a modern café racer should do. However, it also somehow manages to bridge the gap between the Gold Star and the Thruxton. It shares its parallel-twin smoothness with the Triumph, but retains an old-fashioned simplicity to its components like the BSA. This gives it its very own unique personality that sits rather comfortably between the two extremes of café racer history. And yes, unlike the sophisticated Thruxton, it also carries the air of the working-class underdog so essential for a café racer. At least until I change its tyres, install lighter and louder exhausts, and find a way to lose 20 kg.

Nonetheless, between the historical significance of the Gold Star and the modern magnificence of the Thruxton, the Continental GT 650 more than holds its own. Especially since the Gold Star, if you can find one in India, costs more than twice that of the other two put together. And even the Thruxton isn’t exactly what I’d call pocket-friendly. Makes the Indian-made Royal Enfield café racer all the more inviting. Now, did you ever think you’d read such a statement?

Café racers have come a long way from the post-war times of hardcore riders to becoming a means of buying into an iconic motorcycle sub-culture. From blue-collar grit to café-society glam, as it were. However, as history shows us, the Goldstar asked some rather pertinent questions about what a motorcycle should do. And it’s a matter of great happiness that, in their own ways, the Thruxton and the Continental GT are still answering them today. Looking good, going fast.

Huge shout out to our friend, Sajid Syed, for turning up on an early morning with his pride and joy, the Goldie. We keep going because of enthusiasts like him. Also, a big thanks to Vintage Zoroastrian Bikers Of Bombay for their lovely old machines.

[This story was originally published in our February 2019 issue]