It was 1966 and the hallowed British motorcycle industry was on its knees. Associated Motor Cycles, a company formed by the Collier brothers — known for owning the AJS and Matchless marques and had gone on to acquire brands like James, Francis-Barnett and Norton — was dead. Of the lot, Norton was the only AMC-owned brand that was selling enough motorcycles to make any money.

From the ashes of AMC, Norton-Villiers was formed when a company called Manganese Bronze took over. But now, Dennis Poore, the man behind Manganese Bronze, was faced with a daunting task. The American motorcycle market was the biggest in the world at the time and every Yank worth the star-spangled banner fluttering on his porch wanted nothing less than a big-displacement motorcycle.

Royal Enfield was already selling the handsome 750cc Interceptor in the States, and for a time it was actually one of the most powerful motorcycles in the world. Norton had to pull up its socks, but the biggest twin it had was the Atlas, which was essentially an overgrown Dominator – first introduced in 1948 — which was bored out to 750cc.

The cycle parts were the same as the smaller 650 and 500cc Dommies, and that included the Featherbed frame which, albeit garnering a legendary reputation for its handling prowess, was quite dated. The motor vibrated like a jackhammer and when the Atlas was pushed hard, cracks forming in the Reynolds tubing of the frame weren’t uncommon.

Coming up with an all-new engine wasn’t an option; the cost of development and the meagre budget were at odds with each other. So, Poore and team decided to work with what they had. First, the cylinder blocks of the Atlas motor were canted forward to give the engine a dynamic stance even when the bike was standing still.

But there was still that big thudding niggle called vibration that they had to sort out. The Royal Enfield Interceptor, itself a bored-out motor owing its heritage to the 500 twin from the early post-war years, got rid of that problem by dynamically balancing the cranks at the factory before they went into the engines. This made them probably the smoothest of the big Brit twins at the time, but the process took substantial time on the production line and needed skilled manpower to implement.

A smart engineer by the name of Dr. Stefan Bauer, who had worked with Rolls-Royce in the past, came up with the brilliant solution of allowing the motor (which is what the swinging arm bolts hangs from) to go about doing its own jiggle, but isolating it from the rest of the frame through rubber mountings. Called ‘Isolastics’ in Norton-speak, these rubber mountings, along with the frame itself, were actually developed just in time for the new bike to be showcased in the 1967 Earls Court show which was the place to be if you had anything to do with motorcycles.

Poore must have been impressed with it, for the bike went into production with this frame and the new motorcycle’s flanks bore the moniker ‘Commando’. The Commando 750 was quite short lived, however. Make no mistake, it was a decent motorcycle, but it lacked the serious punch that the competition delivered. To add some more oomph to the 750, Norton bumped up the compression to a heady 10:1 from the more sedate 8.9:1 to come up with what was called the ‘Combat’ motor. The result was seven additional ponies over the 56 horses of the stock Commando 750. But these extra horses took their pound of flesh. The limits were pushed to such an extent that cooking this motor was as simple as boiling water, if you didn’t know how to ride this machine. Keeping the throttle pinned wide open all day long was a recipe for sheer disaster, for the bottom ends of these engines couldn’t cope and kept blowing up at such a rate that Norton was flooded with warranty claims.

Despite the advent of the ‘Superblend’ bearings from Norton to eradicate the issue, the damage to the Commando’s reputation was already done and sales dropped drastically. To bolster sales figures, a new 829cc version, called the Commando 850, was announced in 1973, and was created by boring out the 750 even further, with the compression ratio having been brought down back to 8.9:1 to ensure reliability. By the next year, the older 750 was dropped from the Norton line up (although the sporty short-stroke John Player Norton race replica sold briefly at another point in time) and in 1975, the final iteration of the Commando, christened with the Mark III suffix, was launched with an electric boot, discs brakes on both wheels, modifications to the air induction system and a move of the gear shifter to the left to comply with the new US laws. The Isolastic engine mounting was tweaked, too, and this change drastically brought down the time to adjust them from half a day to about half an hour, depending on how good the person undertaking the task was with his tools.

The 850 motor was designed for sheer power and torque, with company claims pegged at 58 bhp and 6.64 kgm respectively. This was amazing once one realised that this was in essence an overgrown pre-unit Dommie motor that was injected with copious amounts of testosterone. Heck, even the 4-speed AMC gearbox of the Commando was previously used on almost all of the AMC machines, both singles and twins, since 1956.

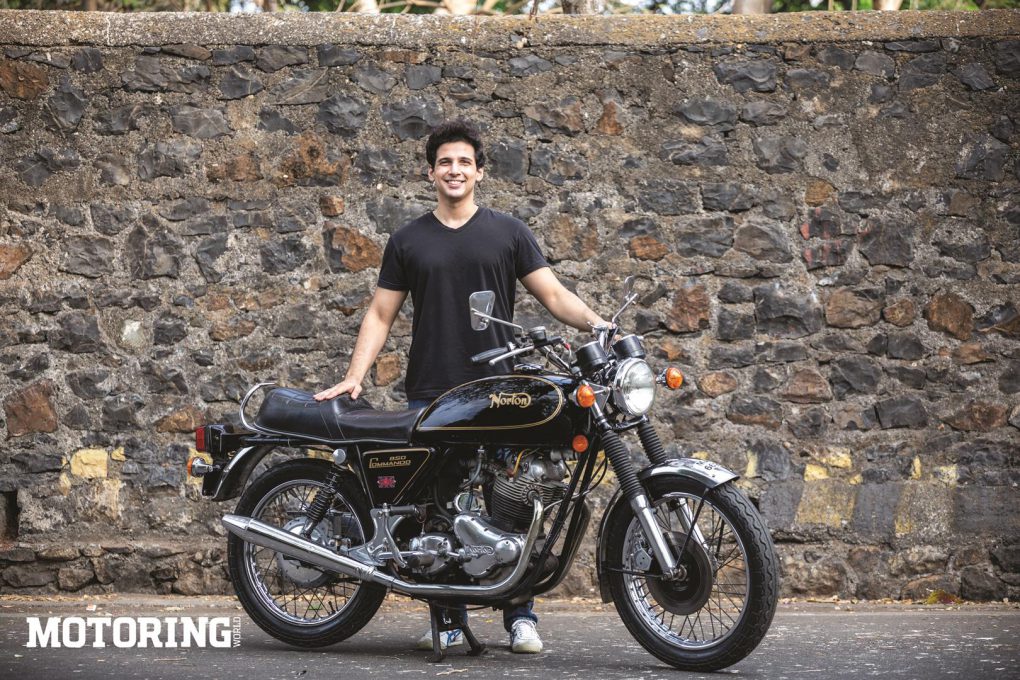

The Commando we had the opportunity of swinging our legs over in order to grace these pages was built in 1973. Presently owned by Xereus Zend, who happens to be an avid British motorcycle enthusiast, the Norton is most definitely the prize amongst his collection of coveted classic machinery. Justifiably so, too, since this is probably one of the only Nortons of its kind in India. But rarity isn’t the only reason why the Commando is desirable.

As with any old Brit bike, the starting ritual is best explained by the owner, because each motorcycle seems to like some things and abhor others, and no two bikes seem to be in agreement with what they commonly favour. This Norton liked the throttle opened a smidgeon. By the way, ten ‘smidgeons’ make a ‘tad’. It’s imperative to get well acquainted with these units of measurement that apply only to vintage and classic British motorcycles if you intend to spend time with them.

With a guttural growl, the Commando sprang to life. It took a fair bit of effort getting the motor to spin up with the kick starter to get it going. My kneecap’s ouchometer definitely swung its needle into the red zone, with my Triumph twins safely registering readings in the green. This was a sheer sign of what this motor was built for.

The effectiveness of the Islolastics became evident when one dismounted off the motorcycle and stepped back to look at it from a distance. The engine wobbled and shook, while the rest of the cycle parts barely twitched. It was surreal to look at, almost akin to a chained-up pit bull barking at a deaf man walking by. And whilst riding it, the only vibes that I felt were a slight buzz on the handlebar grips. This was quite surprising, given the fact that the Commando 850 made do without a counterbalancer or even crank balancing from the factory.

All that shove was great and the frame held the bike tracking true to the lines I pointed it towards. But hurling it downhill from the Hanging Gardens in Mumbai, I called in the service of the lone solid disc at the fore, bitten onto by a Lockheed single-pot caliper, and it felt like trying to call someone in Antarctica with a string telephone. There was no feedback whatsoever, and despite pulling the lever in as far as it went, the speed seemed to diminish in multiples of zero. The rear drum, however, kicked in effectively and slowed both bike and rider enough for the latter to regain the colour in his flushed face. The lack of bite and feel from the front disc could be down to the fact that Xereus was yet to fit the new brake pads he had received a few days ago and also one must remember that when this Norton was built, drums were still pretty much the norm. Disc brakes were yet to be perfected and still the preserve of the upper echelons of motorcycling.

The Norton was a brilliant motorcycle that was brash and bold and needed real men, with hairy chests and calloused hands the size of spades, to extract its full potential. It was the last stand from the old guard and the ultimate specimen in the evolution of the ubiquitous British parallel-twin which began with Edward Turner’s Triumph Speed Twin many decades prior. But the Japanese had already landed onto American shores with their multi-cylinder motorcycles like the Honda CB 750 that could be ridden by just about anyone. Unfortunately for Norton and its ilk, the onslaught from the Orient was just far too strong, and the Commando in its final Mark III avatar was laid to rest in 1977, and Dennis Poore and his team’s valiant efforts died with it. The age of the Universal Japanese Machine had begun.

A big thank you to Xereus Zend for allowing us to feature his brilliant Norton Commando. Also, he’s part of the Vintage Zoroastrian Bikers Of Bombay.

PHOTOS Sujai Rajapaul