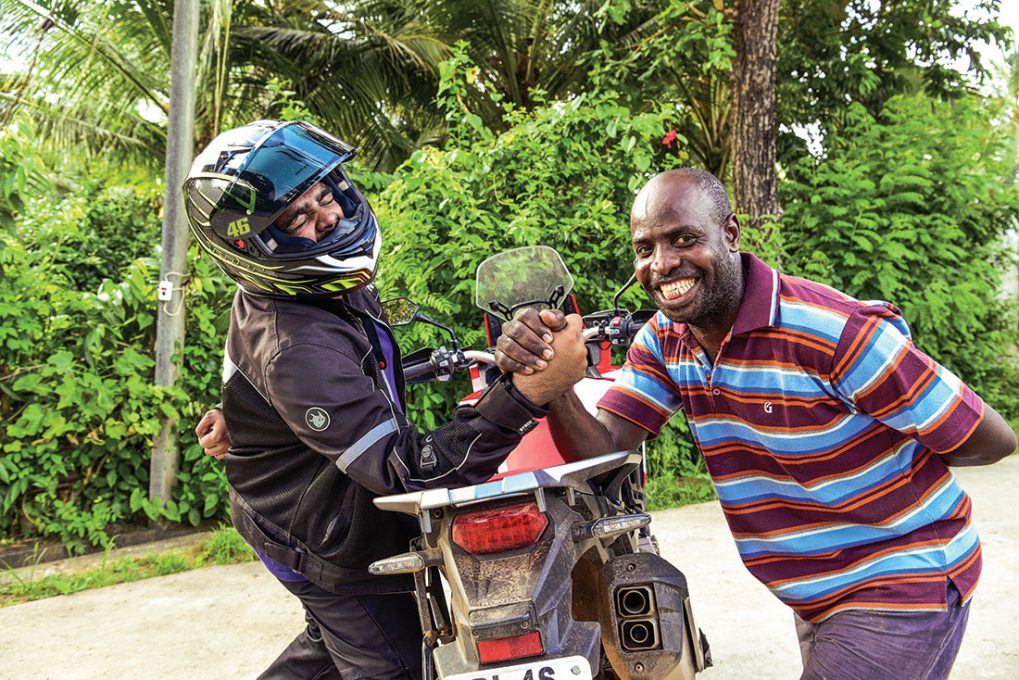

The night before was nothing like this warm, happy picture you see here. Nobody was laughing in the grimly lit hotel room I had hesitantly walked into, and I certainly wasn’t when the lights went out well past midnight amidst a severe thunderstorm. Seated uncomfortably on a plastic chair, I had sat across one Paraza Yasharahla OliverSrson, a man with an acceptable New York accent who, chomping on three pomegranates in quick succession, looked straight out of Botswana or Namibia. To my deeply conditioned Indian eye, there’s no difference between the two. It didn’t really matter in that moment, I suppose. He wasn’t from either, anyway.

What on Earth was I doing in the hotel room of a stranger who looked nothing like me, with a name unlike any other I’d heard before, in the dead of the night, that too? I think I kept asking myself that question every five minutes or so as well. Paraza was a well-meaning American national but years of ingrained racism made it hard for me to think so at that time. Not helping was his broad, beefy frame or that he was wearing an Agbada, a traditional African robe. The colour of his skin overshadowed his patience with answering all my vague line of inquiry. I didn’t know my experiments with discovery would start off with fighting myself. This was a first.

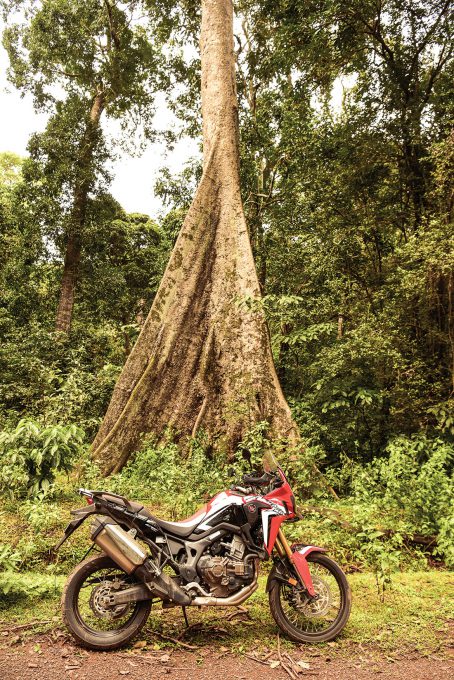

Earlier that morning, I had set off from Mumbai on the Honda CRF1000L Africa Twin in search of an unheard of (or unspoken of, at least) African settlement. Google had been of little help in my week-long research leading up to the ride although I did find my answer tucked away beyond the fourth page of search results. I was looking for the Siddi people. A motorcycle and a community, both genetically African, both thrust into India and left to figure it all out. The Africa Twin was destined to make it here.

The first of the Siddis, originally merchants and sailors from the African Great Lakes region which envelopes Burundi, Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, are believed to have stepped on Indian soil in the year 628 AD. The documented history of the Siddis’ arrival, however, correlates it with the beginning of the Arab Islamic invasion of the Indian subcontinent in 712 AD. These were early instances and bore a defining impact on India, particularly with the establishment of a few Siddi principalities, such as Janjira State in Konkan Maharashtra (the popular Janjira island fort is built by the Abyssinian Siddis) and Jafarabad State in Kathiawar (Gujarat). The Siddis, subsequently allies of the Mughal empire, maintained a stronghold over the Konkan region, defeating the Marathas and even keeping the British empire at bay, for the better part of the millennium. It was, in fact, only in 1948 that Janjira finally acceded to the Bombay Presidency, under the rigid provisions of independent India.

The real influx of the Siddis, however, began with the Portuguese invasion of India in the early 1500s. This time, the Siddis were brought to India (and, around the same time, to other parts of the world, too) as slaves and it’s the descendents of this prophetically cursed tribe that I was looking for. Now reduced to the lowliest of Scheduled Tribes in the states of Gujarat, Karnataka, Goa and the Union Territory of Daman and Diu, the Siddis of today are mostly concentrated in encroached forested areas. I really didn’t know how I was going to find them, or if I was going to find them at all.

This was actually my first really long ride on a full-size adventure motorcycle and I was, naturally, excited about it. That the Africa Twin has made a quick entry into my diary of motorcycle favourites is public knowledge and I really wanted to experience, first hand, everything about an adventure tourer my scattered encounters and theories always seemed to suggest. The Africa Twin was here for more than that reason, though. This is a motorcycle that gets its name from being a dominant force in the legendary Dakar rally, the most grueling motorsport event in the world. A Japanese motorcycle designed to conquer Africa, and now on sale in India. Quite a sojourn, that!

A 12-hour journey involving few stops, sinister cloud formations and a very cold spell of rain later, we had made it into the town of Yellapur in Northern Karnataka. Suresh, driving a Scorpio graciously loaned to us by Mahindra, was in good spirits, too although he wasn’t too happy about sharing a bed with me. Ours was one of three hotels in a 25 km radius and, apparently, the best of them. A change into dry clothes and a good dinner later, we decided to call it an early night. So far, we hadn’t made any contact with the Siddis. I couldn’t sleep, despite the tiredness of the day. The hotel’s receptionist had slipped in a bit of information on discovering the purpose of our visit and I decided to build on it. Our neighbours were, apparently, a group of Siddis who had travelled from Afghanistan and America and they were here for a re-orientation programme of sorts. My weatherproof Yamaha wrist watch said 11 o’clock flat, so I knocked on the door next to ours with my best ‘I really regret doing so’ face on. Impolite, but I had to take a chance.

Our conversation got into its third hour when the lights went out and the racism (or the fear of unknown intentions, at least) kicked in strongest. Paraza had spoken of religion and the sacred prophecy believed to be the Siddis’ present misery, and while all of it was insightful and genuinely interesting, it didn’t help my agenda. I would have been patient if I didn’t have to return the motorcycle in two days. The clock was ticking. I went to bed.

We dragged our luggage out of our basement room later than we had planned. I just couldn’t get myself to wake up early and now, we had barely half a day to figure it all out. Today, we’d be be venturing into the unknown.

A gentle tap on the shoulder came as an unexpected but welcome breakthrough. It came from a man with a frame bigger than mine although he was disarmingly humble from the instant. In his KTM t-shirt and flanked by his wife, Vidya, an equally curious and pleasant personality, he walked up and introduced himself, announcing he was completely besotted with the Africa Twin. So was I, I told him, and we soon found ourselves across the breakfast table, sharing several rounds of crispy dosas and hot coffee over motorcycling banter. It’s amazing how much even just a parked motorcycle can do, right?

I had barely explained the purpose of our visit to him before he excused himself, got on his phone and returned to the table announcing he had everything covered. We found ourselves in the local MLA, A H Shivaram’s office right after breakfast, albeit in the basement parking of his office. I was asked to wait there as Jayanth drew an important-looking person in his late forties to the side and briefed him, in chaste Kannada (or maybe it wasn’t – how was I to know?), about what we were on about. The talkative ‘henchmen’ I was surrounded by were abrasive in their comments towards the Africa Twin but I absorbed it since they didn’t mean harm and I also had no reference for how well I’d perform in a fist fight.

An hour later, we were snaking our way through a small slip road of sorts. To either side of us was a dense forest with gigantic trees and I was jittery despite the ample daylight. This, clearly, wasn’t a very popular route although I felt at ease on the Africa Twin, which was entirely unaffected by the intermittent potholes. I entertained myself by attempting to ‘yump’ it, rally style, over crests and occasionally stepping off the road and onto the gravelly shoulder. We didn’t have too long a journey ahead of us but I, strangely, felt very lonely. Riding through a forest, home to panthers, leopards, elephants and wild dogs is fascinating but not particularly comforting.

My instincts kicked right back in. I began to imagine that Jayanth was, in fact, a psychopath who had planned all of this meticulously. He was going to knock Suresh out with chloroform, push him out of the driver’s seat, execute a perfect J-turn, and come hurtling towards me, mowing the Africa Twin down with a hard impact. Then, after a thunderous tribal prayer to the jungle gods, his African friends and him would make a barbecue dinner out of Suresh and I and sell the remnants of the Africa Twin to traders in Hubli the next morning. This was his modus operandi and it was flawless, as far as I could tell. I saw the Scorpio’s brake lights. It had come to a halt.

I pulled up next to it and Suresh rolled down the window. They were going into the forest now and Jayanth wanted me to wait while they fetched Benneth, the Siddi leader. What? Wait?! In the middle of a forest? They turned off the road onto a soft, muddy track and, within a moment, were out of sight. Now I was really alone. I have ridden a motorcycle in sub-zero temperatures, through a storm, into a desert, and even to a cyclone-ravaged ghost town but never have I felt so uncomfortable on a motorcycle as I did in this moment. I really just wanted to get out of there. It was a warm, partly sunny day, I was cool within my riding gear and the Africa Twin had really proven to be a beautiful motorcycle. And I was hating all of it.

They returned with Benneth Siddi, a bulky man in a tailored white shirt, was who now riding shotgun with Suresh and Jayanth. I was asked to follow. Okay, maybe it’s not going to happen right away. The ride for the next twenty minutes went back to being cold and lonely. All of the last week’s frail research had come down to this.

We spoke in broken Hindi as we walked along and I learned that the Siddis of today are primarily farmers although a few of them did odd jobs in neighbouring towns as well. The government, to give it due credit, has implemented a few successful schemes to generate employment amongst the Siddis, mainly roping them in for forest-related activities although – Benneth didn’t tell me this; someone else did – the tribe is also infamous for rampant wildlife killings and land encroachment, which has made the authorities wary of them. There are always two sides to a coin. We posed for pictures and while the conversation was uneven, the energy was electric. I have rarely felt more alive, more human. I suppose it happens when strip life down to its minimal best.

The women were a more talkative bunch and most were blatantly expressive about why our being there wasn’t exactly an occasion of joy for them. A handful of people had been there before us and most made promises that were, so far, unfulfilled. It was stressful but I knew I wasn’t the revolutionary they were looking for. Their being here was prophetic and, perhaps, so was mine. Come tomorrow, I would be gone. Back to my own troubles, back to seeking my own silver lining. This is how some things are. I hate being complacent and powerless but, sometimes, I am. This is existence. I don’t think any more needs to be said. I wanted to switch off and leave. The warmth lingered but visibly in its trailing end. It was too good to be true.

We said a lot of goodbyes and shook everyone’s hands and I pulled a small wheelie, perhaps as much to leave them with a vivid imagery as to shake myself up a bit. My helmet felt quieter than usual and I could see, through the towering trees, that the sun had already set in some part of the lowlands. Benneth invited us over for a round of tea and bananas, which we graciously accepted. His house, the only one in the vicinity, was quaint and we sat in the verandah on plastic chairs, a few unwieldy hens and chickens running around, breaking the relaxing silence. Insects croaked in the background as we sipped on the ‘jungle tea’, as Benneth laughingly called it, over a decidedly conclusive conversation. The future of the Siddis isn’t too bright but pitying those less fortunate than yourself is easy. Today, humanity on the whole is riding an imperfect wave and the Siddis, in that scheme of things, will perhaps be the first faces to be wiped off the planet but certainly not the only ones. We’re all awaiting our turn. It’s inevitable.

Jayanth had promised to take us to a picturesque location on our day of return and I really didn’t mind making a late exit from Yellapur. We, his family in tow, rode together and it turned out to be more than an acceptable spot of off-roading, all of which the Africa Twin took in its stride without skipping a beat. It really is a wonderful motorcycle, even more so in how encouraging it is of travel and exploration than by simply being long-legged and inherently virtuous. I was tired to my last bone when we returned to Yellapur, four hours later, but we had a 12-hour journey to Mumbai ahead of us. A quick coffee and warm goodbyes later, we were off. I felt a slight lump in my throat as I stood up on the pegs and rode away but there was nothing I was going to do about it. It’s not always important to fight yourself, I suppose. You will always find something else that will be more deserving of it.