First, a spirited roar on a combination of elements that felt distinctly Italian. The sound from the engine, the tautness of the suspension and the seat, the riding position’s slightly aggressive demands; all those sensations painted a vivid il tricolore in my mind. Then, a frenzied scream on more physically considerate components, typically Japanese. Every lever and every action possessed the feel that comes as standard equipment with the tuning-fork badge from the land of the rising sun. Later, the thought — speed is relative, feel is subjective; relativity and subjectivity both need external factors for any interpretation, and neither is absolute. And if two motorcycles as different in feel as the Aprilia RS 457 and the Yamaha YZF-R3 engage in a fast-road dogfight, what is it that really matters?

On a motorcycle, feel is everything. On a fast motorcycle, FEEL IS EVERYTHING. So, while I clocked more than 160 kph on each bike, the difference was stark. The RS 457’s effortlessness to get past that mark was what surprised me the most. It was that great American aphorism at work — there’s no replacement for displacement. The Aprilia’s cubic capacity is exactly what it says on the label, and it’s quite the blessing, whether it’s outright speed or everyday flexibility. In fifth gear, closing in on the redline, there was still plenty of scope for velocity left; Aprilia’s US website claims a top speed of 193 kph! Between the displacement and the 270° crank, the RS 457 felt more like a V-motor than a parallel-twin, too. And put together with its glorious sound, the Aprilia felt rather special and unlike any Indian-made bike so far.

The RS 457 had a grunty feeling that dominated its riding experience. There was torque everywhere I looked, and that decidedly big-bike gear-shift mechanism took me up and down the rev range to confirm that finding. It worked well enough, though it did throw up a handful of misshifts which made me think that the optional quickshifter may not be a bad idea. That was the only niggle in a package that was otherwise rather dynamic. After all, that fantastic motor was attached to cycle parts thought up by the same company that used to make the RS 250 two-stroke, one of my all-time favourite bikes.

The brakes, the suspension, the tyres — everything worked as well as you’d expect from a sporty Aprilia, which is to say that it was a lesson in how to make a nimble yet stable motorcycle. It was enough for me to rue missing the bike’s first ride on a racetrack. The suspension was firm but far from harsh, and it made the job of going fast as easy as possible. The brakes, which I’d heard suffered from fade at the track, remained sharp and powerful on the road. And the tyres were great, too; my first outing on the TVS Protorqs was a pleasant one. They didn’t seem to protest at any time, whether hard on the brakes or the throttle, so I kept electronic intervention to a minimum from all the choices on offer. Bikes like these don’t really need cost-adding nonsense anyway except ABS. All in all, I was left with the impression that Aprilia has finally made a worthy successor to the RS 250, sacrilegious as the thought may be.

However, the R3 was far from soundly beaten. The Japanese machine’s motor was still as involving as ever. Full disclosure — I’ve spent nearly three years with the first-gen R3 and I still have a soft spot for that motor, but there is no bias at play here. The 180° twin is just that great, offering an alternative emotion to the deluge of 270° parallel-twins out there. I hold a similar opinion on 360° parallel-twins, too, by the way. Since the whole world is gravitating towards parallel-twins, let there at least be diversity in crank angles and firing orders. Otherwise, we run the risk of succumbing to the tactile equivalent of what I call Germanonymity Syndrome, in which you can’t tell one car from the next. Also, ironically, it was Yamaha that first used a 270° crank on a production motorcycle, the TRX850 in 1995. But I digress.

With every twist of the throttle, the R3 sent a high-rpm shiver up and down my spine, sounding very much like half an inline-four. There was also a new burble on the overrun from the exhaust which made downshifts as rewarding as the screaming upshifts. The frantic yet composed nature of the R3 made for days full of redline-stabbing attempts, sure in the knowledge that the bike had my back; that’s something I couldn’t always say for the non-ABS first-gen one. With the new R3’s USD fork, the bike felt way more sorted, too; it was stable all the time, whether in corners or on fast straights. The brakes were still a bit soft for my liking, especially compared to the RS 457’s. However, the Dunlop tyres made up for that with their tenacious grip. In every way, the new R3 felt like a meaningful upgrade to the older one.

Dragged together from 3000 rpm in sixth gear, the RS 457 comfortably growled away from the R3. This bodes well for everyday use, though its riding position was good for a little over an hour in the city. Out on fast roads, though, it wasn’t that bad. However, the R3 was more comfortable everywhere, whether in town or on a top-speed run. I did need to rev it out to get going in a hurry, but by now you must’ve realised that it was an act I didn’t mind repeating as often as I could. Overall, the RS 457 will go fastest, the R3 will go fast the longest. Plus I was reminded on a couple of occasions that even Aprilia’s MotoGP bike keeps conking off far too often for its own good. However, nothing on the RS 457 gave me the impression that things would fall apart anytime soon.

I’ve followed Aprilia’s Instagram page long enough to notice the change in their hashtag; earlier, I’d read the uncapitalised motto as ‘bear acer’. Sometime last year, someone rightly decided to make it ‘#BeARacer’, and I can’t thank them enough for it. That hashtag, by the way, is also what the RS 457 expects you to be. Well, if not be an outright racer, at least to have a physical form and strength approaching one. If, like me, you happen to like a more committed riding triangle, you’ll love the RS 457. And if, again like me, you have an inherent distaste for the use of black as a primary colour on a motorcycle, you… well, you get the picture. How about a yellow-silver paint job instead?

As for the R3, overall, Indonesian-made Japanese felt better designed and finished than the Indian-made Italian. However, most people may like the Aprilia’s colourful TFT screen; it did make the R3’s plain LCD look like my scientific calculator from engineering college. Nonetheless, all TFT screens look the same to me; if it’s not proper needles, I’m not interested. And that’s why I also appreciated the sheer feel (there’s that word again) that the R3 offered. Even after all these years, I firmly believe one thing — somehow, only a Yamaha possesses the engineering finesse that turns into engaging emotion on the road. They’ve been on to something for a while now, and no one else seems to notice that. Or maybe it’s just me. Nonetheless, let’s address the elephant in the garage, shall we?

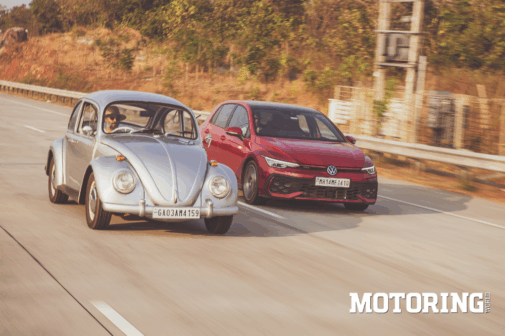

Everywhere, the RS 457 felt like a smaller big bike and the R3 felt like a bigger small bike, and yet they still fall into the same ballpark of perception. The price difference is roughly ₹ 55,000; since the RS 457 is made in India and the R3 is not, you can easily figure out which one carries the monetary handicap. However, all is not lost — the R3 is a proper keeper of a Yamaha, and if you like it, the price should not stop you from getting one. That said, it is now nine (!) years ago since the first R3 came out in 2015, and this R3 was out in 2019, even if we’ve only recently got it. Without question, it’s now time for an R5, perhaps even one made in India, no less. The RS 457 is entertaining proof that it can be done.

In the end, it’s not always about how fast you’re going; more often, it’s about how you’re going fast. You have to decide for yourself between a good deal and a good feel. Speed will find you, one way or another.