Time breaks cleanly in two. There are the years Before Riding, and there are those A.R. Otherwise known as ‘life’. Mine didn’t begin in earnest until then, I see now. Or at least a life composed of moments so unfathomably rich, with their extravagant icing of luck and sensation, they erase everything that came before as so much cardboard posturing. From the moment I felt what it was like to engage first gear, feel that reverberation through the whole of an intricate yet also irreducible system, ending in the rear tire grabbing a piece of pavement in a presage of unlimited sensual potential, I knew I wasn’t going back.

This happened in the Dark Ages. I began riding motorcycles before many of you reading this were born. It was a different world for women then, and especially for women riders. Internally I didn’t, couldn’t, experience anything I was doing on a bike as ‘a woman’ — the act is so elemental it can have nothing to do with gender. Only with a body meeting space through the medium of the mechanical. But those outside me certainly witnessed a woman riding a motorcycle — and let me know it at every turn. It appeared to break some brains as they tried to comprehend the incomprehensible. (Elsewhere I have related some episodes of this towering incredulity, wherein visual evidence could simply not be computed: the toll taker in the middle of the closed highway who accepted coins from my gloved hand as my 500cc engine rumbled beneath me, no one else present at the exchange, eyes wide as he asked, ‘Did you ride that here?’ Or the many men who persisted, when I happened to be riding in the company of a man, in addressing only him — including questions about my bike. I would overhear, at a distance, a query about whether that was an Italian machine, whether was it good, and so on, which allowed me to feel what it was like for sparks to fly from my brain upon attempting to understand the truly bizarre.)

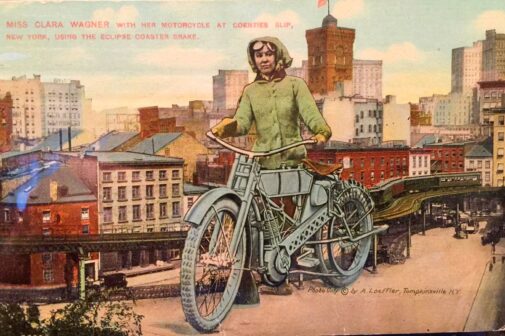

I began researching the history of women in motorcycling, just to prove what I already knew: women have been capable riders since the birth of the sport. What they went through at the dawn of the two-wheeled revolution — during the Stone Age of gender parity, which made my own unenlightened time look like the height of reason — is nothing short of mind-blowing to the contemporary onlooker. Stopped by the police for wearing trousers. Despite successfully enduring a coast-to-coast ride over 5500 miles of largely unpaved road, being prohibited from serving as dispatch riders in the First World War. Becoming the object of dangerous sabotage or race-fixing when they dared to win on early tracks.

It was strange, so many years after the irrefutably grand exploits of the first female adopters of the motorcycle, to ride into a rally or other gatherings of hundreds of riders and see few if any, people who looked like me. On the few occasions I did ride with a group composed only of women — and I say this as a card-carrying nonjoiner type — it is hard to express what I felt. A soaring? A warmth? An otherworldly joy? Yes. It can only be described as a feeling of ecstatic belonging. Without speaking of it, we knew we were profoundly united by the same experiences. These were primarily having the queer the sensation of being disbelieved, in not just ability but our very corporeality; in our attempted erasure from the history as well as the present scene of the endeavour.

As we took the Massachusetts roads together, a group dozens strong who in relays would retrace the cross-country route of sisters Augusta and Adeline Van Buren in that record-breaking 1916 ride on Indian motorcycles — including the first-ever ascent of the 14,109-foot Pikes Peak by women in any motorised vehicle — we were all suffused by a sense that we were one: powerful, capable, a link between past and future. But above all happy to be on motorcycles. A simple yet complex pleasure, socially physically and intellectually at once. I’d bet my last dollar that behind the helmet of every rider I was among that day was a smile as irrepressible as a tropical sunly clubs, venture to gatherings such as Babes Ride Out, where they will bathe in the special happiness that comes with spending a weekend in community with a thousand new friends who implicitly understand each other, or go out of their way to utilise a woman-owned garage such as Brooklyn’s Motorgrrl. It is not to exclude men. It is to not have to explain yourself, just this once.

In the aforementioned Dark Ages, when I began riding, fewer than 10 per cent of my compatriots were female. Now, fully a quarter of Millennial motorcyclists are women, and many of them are doing extraordinary things on bikes — no longer at risk of being arrested for wearing trousers. They are circumnavigating the globe and excelling in competition. They are breaking long-distance records. They are stunt riders with the athletic grace of a prima ballerina and the nerve of a big-wave surfer. They are everything they want to be.

Me, I just want to continue doing what I want: ride. I don’t do it to prove anything to anyone. Well, maybe to myself. What I show myself every time I start the engine is that I am worthy of happiness. The American Declaration of Independence posits ‘certain unalienable Rights’, among them ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’. When I was a child my father made certain I read this correctly. ‘Notice, Melissa, that it does not say happiness should be guaranteed. Only that everyone has the right to pursue happiness. That is what makes a people free.’

Women’s freedom to pursue their happiness, in whatever arena they choose, has been hard-won and always at risk of loss; such is the world. I am particularly grateful that sometimes happiness runs so fast it requires me to twist the throttle a little more insistently. Or it threatens to disappear over the horizon, so I need to ride that much farther in a day. I may never catch it, as my father cautioned, but I keep trying. So long as my pursuit is by motorcycle, I know I am a free woman.