It was the mid-fifties and British motorcycles still ruled the roost across the world. Edward Turner had already launched the Triumph 5T Speed Twin nearly two decades ago and this parallel-twin, along with the later variants such as the Tiger that it had given birth to, had already begun to take the motorcycling world by storm. So much so that almost all of the other Brit motorcycle companies got their designers and engineers furiously working on parallel-twins to take on the 5T.

But one plucky marque, based out of Hall Green in Birmingham, England, refused to go with the crowd. Veloce Limited, started in 1905 by John Goodman, had by the time earned a reputation for high-quality big singles, sold under the brand name Velocette, that were equally adept on both road and track.

Veloce never made a parallel-twin throughout its existence, right from 1905 to 1970 when the company went kaput. They did make a couple of horizontally opposed twins, however, but they were never intended as competition to the plethora of parallel-twins that were being churned out of motorcycle factories all across Britain. Instead, they introduced the Velocette Venom at the 1955 Earls Court Motorcycle Show. A big 500cc single with a square bore and stroke length of 86mm x 86mm which was good enough for about 34 bhp, a whole seven ponies more than that of the Triumph Speed Twin that it was meant to compete with.

Getting all that power out of one pot, albeit a big one, took some ingenuity. But this wasn’t alien to Veloce, especially when one recounts how Veloce was the first manufacturer in the world to use a positive-stop foot gear change on its production motorcycles. One way to make power was to reduce the mass of the engine internals. An overhead-cam setup negates the need for heavy cam followers, pushrods and rockers.

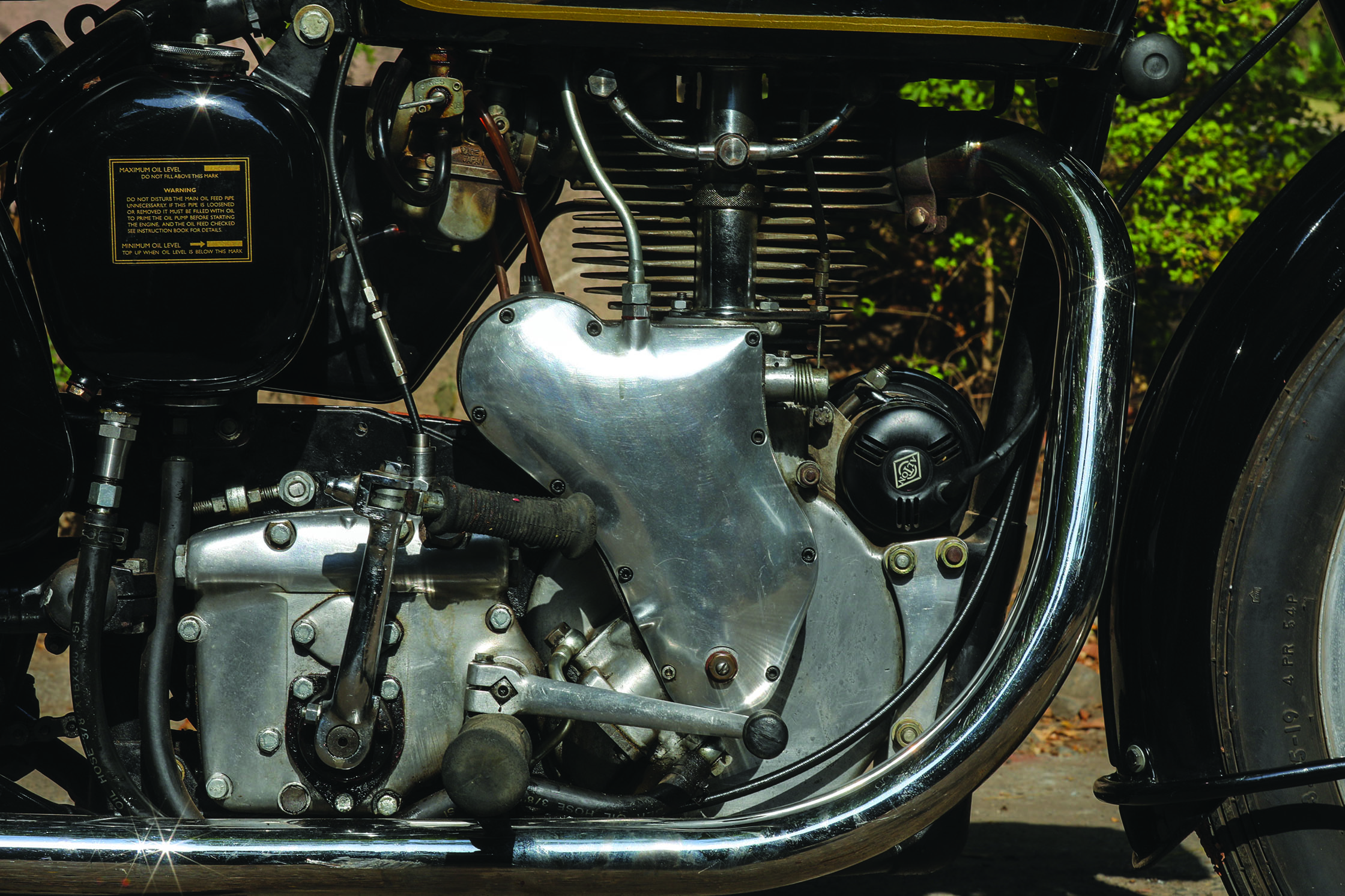

But designing such an engine, and subsequently manufacturing it, would be an expensive proposition. What the brilliant engineers at Veloce did, instead, was position the cams high up in the timing chest. This way, the lengths of the pushrods were reduced drastically, and thus they weighed significantly less than full-length units. This engineering solution indirectly gave birth to a styling element that became synonymous with Velocettes, the timing cover that looked strikingly similar to the African continent on the map.

Another departure from the norm is the way the powertrain is set up. Unlike most other motorcycles which have the clutch located after the gearbox, the Velocette Venom’s clutch pack is located in between the engine and the gearbox. This allows easy access to the primary sprocket, facilitating quick changes to the gearing, but at the cost of gaining easy access to the clutch.

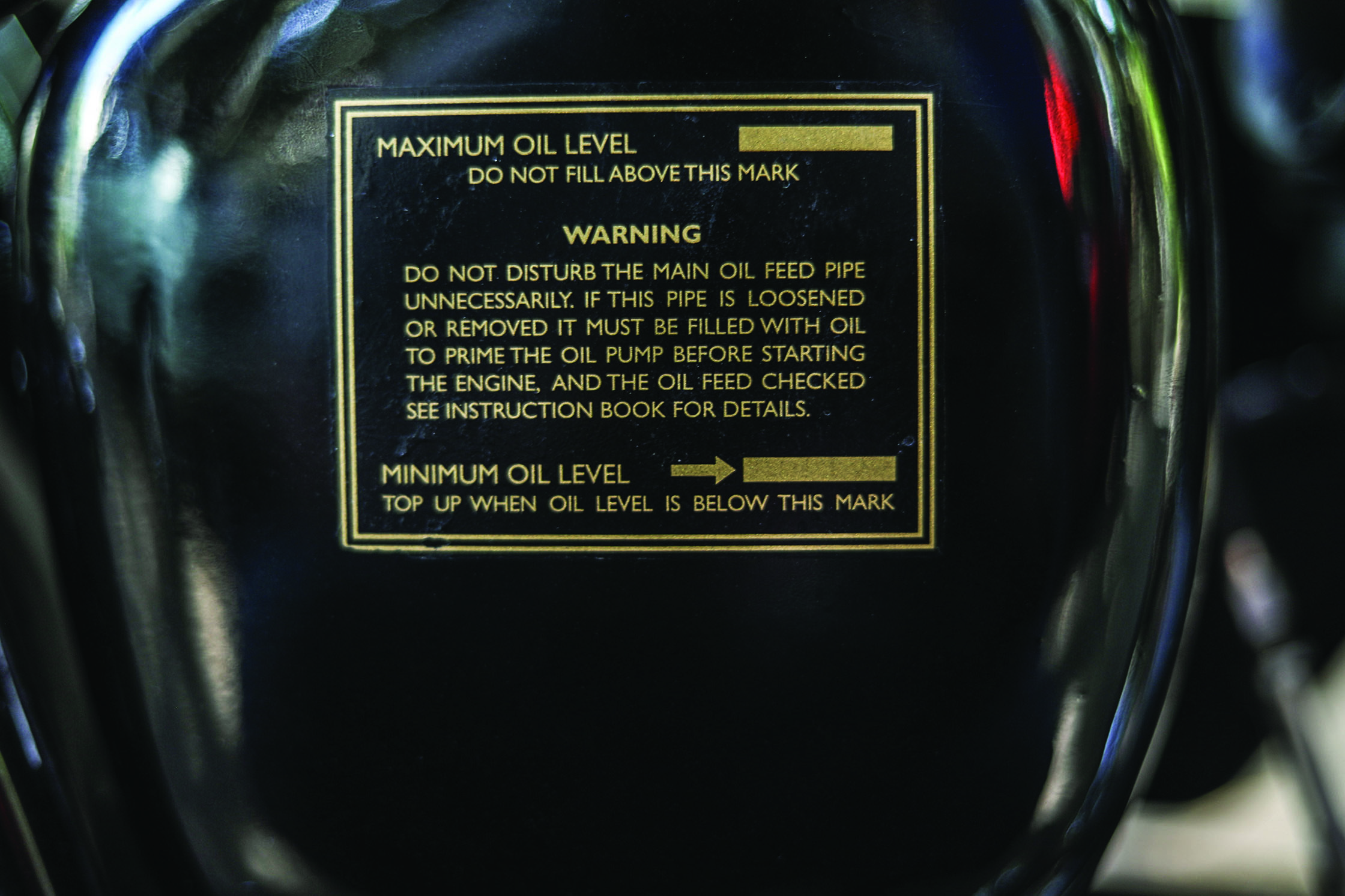

The clutch is again quite, how do I put it, eccentric. Instead of a pushrod separating the plates, the Venom’s clutch is disengaged through an elaborate linkage, the last of which rocks back and forth on a pin, acting like a cam that pushes a rod onto the thrust cup, which in turn exerts pressure on to three thrust pins that push the plates apart against spring tension. If that sounds quite complex, well, there’s a reason why the motorcycle press at the time labelled the Velocettes as steeds for engineers because it took nothing short of exemplary technical knowhow to keep these bikes in fine fettle.

I remember going through a Velocette owner’s handbook a few years ago, although that was of a Viper, the 350cc sibling of the Venom. The book had an extensive chapter that dealt solely with the starting ritual to get that big single piston going. So when we arrived at Rahul Manthalkar’s home in Pune, with his gleaming Venom parked outside, replete with a gleaming chromed tank and shiny black paintwork, I had some serious apprehensions.

Yes, I’ve ridden a Venom in the past but anyone who has had even a passing encounter with British motorcycles will attest how different they are to each other. Even bikes of the same model and year have their individual quirks. Some like no throttle when they’re being kicked over. And some need a smidgeon. And that’s only the beginning.

The pleasantries were exchanged and it was time to put my foot where my mouth was. I said a quick prayer to the British God of Motorcycles — who, I suspect, had a right calf as thick as a redwood tree — and I switched on the fuel, pulled in the clutch and kicked the engine over a couple of times to free the plates. Then, releasing the clutch, I nudged the kick downwards till I found compression, pulled in the decompressor lever to coax the piston just past top dead centre, and then gave a heaving kick. All that effort resulted in muffled wheeze from the carburettor.

Damn. This was going to be harder than I thought. Rahul took over and a couple of kicks later, the motor came to life. Not one to give up, I pulled in the decompressor to kill the engine and proceeded to have another go at getting this big single to sing her song. This time around, using the exact same procedure that I had enumerated above, the engine started and settled into a nice even idle, chuffing elegantly through the beautiful chromed fishtail exhaust, another Velocette trademark.

I swung my leg over the motorcycle and the controls found my hands. Most British bikes of the era sport comfortable ergonomics and the Venom is no different. The rider triangle is perfect for long hours in the saddle and yet, one has tremendous leeway to stretch out into a more aerodynamic crouch.

The chrome lever on the left-hand side of the handlebar was tugged in and I engaged the first cog of the 4-speed gearbox by pulling up the gearshift lever with the toe end of my right boot. The clutch pull of this Venom was by far the lightest that I have ever experience on any motorcycle till date. This is no empty hyperbole; you have to experience it to believe it.

Fed it some throttle and the big thumper pulled away cleanly with the need for only the slightest of clutch slippage. As speeds climbed, subsequent upshifts needed absolutely no clutch work. Before I knew it, I had shifted up to top gear, going through every gear with the grace and panache of a renowned ballerina. That was only because of slick-shifting gearbox and the feather-light clutch. I know I repeat myself, but the clutch was so wispy that it would put a lot of modern motorcycles to shame.

Although this specimen is all of 63 years old, it accelerates with an alacrity pretty much on par with a modern 250. But no modern quarter-litre rice burner could ever come close to the Venom’s soundtrack. Modern legislation has killed the motorcycle’s song, but the Venom is a resounding reminder of how glorious motorcycles once sounded. The rorty note being blasted from the fishtail combined with a very purposeful induction roar and mechanical clicking from the engine resulted in what would be Bach’s magnum opus had he been a motorcycle aficionado

I didn’t get an opportunity to squeeze the Venom through some serious corners, and the Pune traffic was already out in strength for me to attack roundabouts with any semblance of anger. What I did do, however, was put the Venom through some spirited directional changes and it did my bidding with stunning accuracy. This was quite remarkable from what was essentially a heavy brazed frame that had some attributes borrowed from ancient bicycle frame design. The Veloce peculiarity could also be seen from how the swinging arm was constructed.

Conventional motorcycle swingarms, sprung from twin shocks, generally consist of two arms that are welded onto a pipe through which a shaft is bolted on, pinning the arm in the frame from where it pivots. The Venom’s swinging arm actually consisted of two individual arms that were merely clamped on to the frame from each end — whilst hung from a duet of hydraulically damped shocks that could be slanted by sliding their top along special guides to compensate for the rider’s weight — which meant aligning them could be a job cut out for very patient and capable people.

The Venom was a motorcycle for experts and the old Veloce marketing spiel highlighted that fact. It took a sizeable premium over the competition to buy, a lot more knowhow to maintain and demanded experience from the riders who rode it. It wasn’t intended to be a motorcycle for the masses and throughout its 15-year production run, a little more than 5000 were made in total.

The Venom later grew into the mighty Thruxton which was even more mental with a higher-compression piston, a factory gas-flowed head and the like to squeeze out even more dementia from this motor. A suitably prepped machine managed to complete 3840 miles in 24 hours on a banked track in France in 1961, averaging an imposing 160 kph all through which continues to be a feat even to this day.

The Venom might be rare and lustworthy, but its true claim to fame lies in how the small company that conceived it built a world beater by sticking with what they were good at. The Venom is proof of what can be achieved when one chooses to stand proudly apart from the crowd.

A big thank you to Rahul Manthalkar for allowing us to have a go on his fantastic Venom!