Early one morning, in Bengaluru, I got into my car and Google-mapped a route to KP Subbaiah’s house. He owns the lovely Daimler DB18 you see in these pages, and had readily agreed to let me feature it, with the sort of easy grace that seems to come naturally to a lot of vintage vehicle owners. It was a Sunday, so traffic was sparse, but the going was still a little slow because of the horrendous state of Bengaluru’s roads; every single one that I encountered appeared to have been dug up and then just left in that state, as if the contractors had decided that it wasn’t worth their while after all.

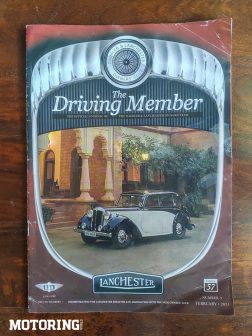

The less-than-rapid pace gave me time to wonder about the car whose acquaintance I was about to make. I’d seen photographs of it that Subbaiah had sent, and of course they floored me; the Daimler looked absolutely pristine, like it had just purred out of a showroom. I experienced the tingling of excitement I always feel just before I’m about to interact with a vintage machine, something that doesn’t appear in quite the same way where modern ones are concerned; there’s something about a piece of history that just hits different, as they say. When I finally pulled up to Subbaiah’s home, the Daimler was already parked outside it with him standing alongside, very much like a proud parent. It glowed softly in the dappled light, and I sensed that a great story resided in it. I was right.

Subbaiah has impeccable vintage-car genes. He owns two other vintage cars, his father is a founding member of the Karnataka Vintage and Classic Car Club, and a family friend, Sripathi Rao, encouraged him to begin collecting cars. One of Subbaiah’s bucket-list items was to own a car from the stables of the erstwhile maharaja of Mysore, especially one with an MYB registration plate. In 2016, Rao told Subbaiah that just such a vehicle was up for sale — a 1947 Daimler DB18, with the registration number MYB 89. The car had been acquired by a gentleman named KN Srinivasan in 1957 from his former classmate, who just happened to be the former maharaja of Mysore. The Daimler had stayed within Srinivasan’s family for six decades, and had been carefully stored in a garage after his passing by his daughter.

In 2016, she decided that it would be best if the car were to go to another owner, someone who would shower it with the TLC that it deserved. Sripathi Rao convinced her that Subbaiah was the ideal person for this; his passion for vintage cars sealed the deal, as did the fact that the car would remain in its home state of Karnataka. In August 2016, the deal was sealed, the garage was opened, and the Daimler was taken out of it for the first time in 15 years. Subbaiah says it was beautifully preserved and in original condition even after all that time, but he decided that only a full ground-up restoration would do for such a wonderful car. The car was stripped bare and the process took four years, with the mechanicals entrusted to Bengaluru-based Christopher Rodricks, who cut his teeth in Australia with a firm that specialised in restoring Rolls-Royces and Jaguars; the body work was carried out at Jalopy Shop, also in Bengaluru. Appropriately, the fully restored car arrived at Subbaiah’s home on his birthday in December 2020, and since then he says he has put over 1500 km on the clock.

I’m not surprised he’s done so. Just look at this car — if I had it parked in my garage, I’d want to go out and drive it as much as possible, too. Subbaiah’s car is a 1947 model, with four-door bodywork by Mulliners straight from the factory (pre-war cars were usually offered as chassis only, with coachbuilders of the buyer’s choice carrying out the bodywork). Its fresh-from-the-showroom look hides the incredible amount of effort that went into the restoration process — every part was removed, various parts had to be ordered from abroad and several upgrades had to be made to ‘modernise’ the car while retaining its original character.

For example, Subbaiah decided to change the wiring from positive to negative and to also add 3M insulating material on the body for heat and damp retardation. Another (somewhat mischievous) touch was the addition of indicators off a KTM Duke. These slim units were discreetly fitted under the front and rear fenders, so that other road users could see when the car was about to turn; the standard semaphore units in the upper B posts were too much of a distraction to passers-by, and also ran the risk of being snapped off.

The DB18 exemplifies British design. It’s stately, elegant, rounded and understated (for its time, anyway — now it stands out for a mile), and the cream and black colour combination works wonderfully well. Its dimensions are nigh on perfect — large without being imposing, with just the right touch of sportiness to give it some oomph. The cabin is simple and sumptuous at the same time, largely thanks to the quality of restoration work that went into it; I was immediately put in mind of a P.G. Wodehouse novel as soon as I got into it via one of the large doors. The rich red leather and polished wood has that typical vintage-car aroma, and you sink into the seats almost with a sigh of pleasure; the rear seats are so comfortable you could quickly fall asleep in them, and there’s acres of room at the back for the lucky passengers to sprawl themselves out. Additionally, you can see the semaphores from here if they’re used, which you can’t do from the front seat.

Up ahead, the driver’s and front passenger’s seats are almost as comfortable, even though they’re quite close together. A sunroof and windscreen-lift lever function as additional ‘air-conditioning’ apart from the windows, if the going gets a little hot; the levers and switches fall perfectly to hand, and the cream dials ooze charm — there’s a speedometer, clock, voltmeter and fuel gauge. The three-spoke steering wheel feels a touch spindly if you’re used to modern steering wheels, but it feels great in your hands. This is the very epitome of a functional yet cosseting cabin — there’s not a single extraneous element in it.

Under the Daimler’s stately bonnet is a 2522cc OHV inline-six engine putting out a relaxed 70 bhp and 16 kgm; the engine’s cubic capacity was the reason the DB was also known as the Daimler 2 1/2-litre. The power plant turns over and fires up without a hint of drama, settling into a creamy purr at idle, and you immediately get the feeling that this is a car in which long journeys would be a pleasure (Subbaiah regularly takes it on 300-km round trips). The engine is mated to a fluid flywheel 4-speed Wilson ‘pre-selector’ gearbox, which is a superb little thing, kind of like the AMT of its time.

What it does, essentially, is let you ‘pre-select’ the next gear using the shifter mounted on the steering column, with the transmission staying in the current gear until you press the ‘gear change pedal’, located where the clutch pedal usually is. Back in the day, this technology did away with the need to double de-clutch a non-synchromesh manual transmission, and shift times were also typically faster. Added advantages were that these gearboxes were lighter and could handle greater power outputs, and ‘pre-selectors’ were quite popular before true automatic transmissions came into use. It does take a little time to get used to operating this system, but once you do, it’s totally hassle-free.

On the move, the Daimler glides along, seemingly without a care in the world. Acceleration is quite brisk, and this particular model is capable of a 122-kph top speed, given enough road and determination on the driver’s part. The most striking aspect of driving this car is its butter-smoothness and calm demeanour; at no point does it feel stressed or out of breath, and that feeling rubs off on the passengers, lulling them into a Sunday-afternoon brunch state of mind. The torque and gearing are such that you could probably be in fourth and still be able to get going from a standstill, and the sight of the narrow bonnet ahead of you making its way down the road is most satisfying.

Belying its size and bulk, this car is a breeze to steer and handle. The steering feels accurate and positive, and slow speed manoeuvres are no problem at all. The ride quality is fantastic, thanks to the coil spring independent front suspension and a semi-elliptical setup at the rear; you can barely feel any bumps in the road (yes, even on Bengaluru’s roads), which must have been part of the reason this car was so popular with the maharajas of the time. The brakes must be made special mention of — a lot of vintage vehicles can give you heart-in-mouth moments when you attempt to slow down, but these brakes are superb, hauling the Daimler in with confidence.

As we headed back to Subbaiah’s house for some very welcome filter coffee, I wished that I could have taken the sort of drive in the Daimler that he often does (he’s driven to Goa and back in his Beetle, but that’s another story). It’s the kind of car that makes you fall in love with it very easily, and it had certainly done a number on me in the short time that I spent in it. Subbaiah, generous as always, made me an open offer to come and spend more time with it the next time I was in Bengaluru, and I think a trip to the Garden City would be worth it just for that.

We’d like to thank KP Subbaiah for agreeing to let us feature his beautiful Daimler DB18.