‘Study in Poland,’ read a vinyl advertisement banner, dangling loosely on the locked gate. You must have to be really desperate to get out, if Poland was your migratory residence of choice. The more pressing scenario at that time, however, was the locked gate itself. We’d spent the better part of a morning to get to Dandi, Gujarat, and to be locked out of its only beach set off panic alarms. I decided to consult the head of the security arrangement, a must for what is arguably the most important beach in terms of India’s history and freedom struggle.

Unfortunately, despite looking hard and all over, there was no head of security to meet. There was, in fact, no security at all. The idea of taking two British icons to Dandi, a town that marked the beginning of a globally recognised anti-British rule movement, was a cheeky one, but we thought of it as no more than just that. In 1930, Mahatma Gandhi had set off on the Dandi March from his abode, the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, to protest against the salt tax levied upon Indian salt producers by the East India Company. This form of non-violent disobedience made headlines around the world and was a major setback, even though the offending parties barely admitted it, to the British regime. Twenty-four days later, Gandhi, along with thousands of his followers, made it to Dandi and, in a splendid act of defiance, produced salt from the sea water by himself.

Being here today was, therefore, overwhelming. I’d ridden the Triumph Bonneville Bobber down from Mumbai on a mildly overcast morning, with only a magnetic tank bag for company, stuffed with essentials such as a spare visor, my phone and wallet, and, oddly enough, a Swiss Army knife. Just in case, you know? Everything else I decided to lug along went into the car which happened to be (by no coincidence, of course) a Mini Cooper S JCW. Rather, a very bright yellow Mini Cooper S with a racy exhaust note. The brief was simple — easy on the highway, an elaborate breakfast midway and no stops other than for fuel. Easy said, easy done.

On the single-seat-only Bobber, I maintained a 90-kph cruising speed, at which it was completely at ease, with the pronounced thump of its tailpipes making for a good, progressive soundtrack. The Mini, out of Motoring’s tried-and-tested highway code, stayed in the Bobber’s mirrors at all times, its occupants (Kyle and Janak) thoroughly entertained by its funky interior. Okay, so Janak slept through most of the 220-km drive (and through the next two days), but that was justified since there wasn’t much to look at in terms of scenery.

After a heavy lunch and mild procrastination, we set off to discover the historically-paramount coastal town we’d only read about in poorly illustrated textbooks. I hopped into the Mini this time around and Janak was more than happy about getting on the Bobber although he didn’t look too pleased about getting into my riding pants. I played navigator to Kyle who, having spent the better part of the morning in the Mini, reeled off his thoughts on the car. The toggle switches were a huge hit with him, almost as much as the peppy 2.0-litre four-pot motor and while the John Cooper Works package being holed up into one of the cupholders did leave him perplexed, he didn’t seem to mind being in the driver’s seat one bit. Now, while I do struggle to justify the Mini’s price tag, I still think it’s a special car that’s extremely fun to drive and one that’s reasonably practical, too.

From the Mini’s passenger seat and with our battered Canon strapped firmly in hand, I took in the sights, with Janak intermittently blocking most of it with the gorgeous Triumph. One railway crossing later, we were on a two-lane strip of tarmac that called itself the Dandi Path. ‘Wow! So he must’ve walked past all of this? Do you think this house must’ve been around then?’ However, the Dandi Path is entirely unremarkable in the sense that if you took the known history out of it, there’s nothing by measure of visual reference. It looks like just another road, save for the milestones that have etched onto them a charkha, Gandhi’s beloved spinning wheel. Surely, Dandi would have more in store for us explorers, I thought to myself.

I thought wrong. A few minutes later, we’d parked nose-front outside the aforementioned locked gate and that, at that moment, at least, seemed like a massive blow to our curiosity.

Desperate, we decided to park the machines and head to the beach anyway. The beach is particularly long and the sea seemed choppy and aggressive. That didn’t keep the small groups of tourists from venturing in, something I figured was the case around the year. I couldn’t find any statistics to prove it, but the amount of litter we tiptoed through was enough of an indication. Every square inch of the beach was covered with empty chip packets — can you believe it?

You would expect this sort of thing in perhaps Goa, which is full of inebriated revellers, but here? It’s appalling. I know we are a third-world country, but I didn’t know we could be this shameless about it. I also didn’t know there were these many flavours of Lay’s chips, but, at least in this aspect, Dandi proved educative. We turned our backs to the sea and walked towards the machines. The Bobber, as was the case with my previous encounter with it as well, is quick to attract eyeballs and had a small crowd gathered around it. Despite its compactness and simplicity of design, everyone around knows it’s a ‘big bike’ and that’s good enough for most. Thanks to a faint spell of rain along the way, the Bobber had covered itself (and Janak) up with a lot of muck and, somehow, it looked even more purposeful with those streaks of mud and dead bugs on its headlight and fork. I cannot resist the Che Guevara references when I look at the Bobber and, given the current scheme of things in Dandi, I was hoping Janak would turn into some sort of revolutionary icon and bring about a wave of change. My hopes were quickly punctured when I saw him clicking a selfie with the beach, however. Sigh.

Our spirits slumped, we drove off in another direction and, with a stroke of luck, our search had led us to a temple which, by the look of it, seemed to have sprung up relatively recently although it did had an admirable tree cover and no visible monument or structure. We did spot a gigantic cutout of the Mahatma, dressed typically in khadi, resting on a similarly gigantic banyan tree. And the gate was locked again. With a cloud of depression firmly setting in, we drove further into the lifeless lane with unkempt shrubbery lining its sides. In the distance was a gate — yes, yet another one — with the tricolour painted on its wooden frame. It was locked.

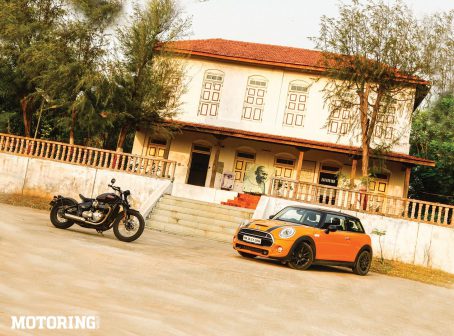

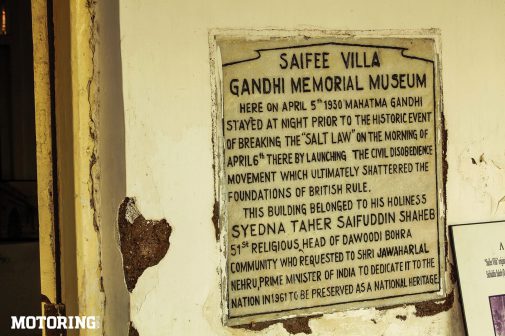

I hollered for someone of some relevance and, out of nowhere, materialised one Raman Solanki, who looked in better spirits than the house did. Hands folded into a perfect namaste, he greeted and ushered us into the premises. We now stood in the courtyard of the Saifee Villa and while the two giant monuments were certain hints, we still weren’t sure why we were here. This was the house, Raman explained, where the Mahatma had stayed for the days that he was in Dandi. At the time, the house belonged to Syedna Taher Saifuddin, the 51st religious leader of the Dawoodi Bohra community, a sect in Shia Islam. It was he who had hosted Gandhi during his act of defiance, as a gesture of hospitality and also in view of his security. Saifee Villa is beautiful. If it’s so beautiful today, can you imagine what it must have been like back in the day? A generous porch, two levels of residential accommodation, large, airy rooms, all looking out to what is now landfill (for a memorial which should be built within a few years) but — shockingly — used to be the sea! So, this was where the salt satyagraha happened and not the beach we were at earlier. Raman kept talking us through every nook and cranny of the house while we let out collective gasps, diligently referring to Gandhi as ‘bapu’ (father, in casual Gujarati). It seemed far more personal and comfortable. We don’t address any representative of the country this way anymore, do we?

In 1961, the Syedna dedicated Saifee Villa to the country and, after a small ceremony in the company of Jawaharlal Nehru, the then Prime Minister of India, officially handed over the papers of the house, to declare it as a pillar of India’s heritage. The Syedna had believed that a house like this belonged to the whole nation and not just one community and so, private ownership of it would be grossly unjust. Yes, there indeed was a time when people did think beyond themselves, beyond materialism. But something, somewhere, did go wrong. It’s not that hard to tell, is it?

While I got busy with the camera, Janak took a nap on the porch and Kyle, ever the one with an eye for anything old, took a closer look at the house and its disappointing state of affairs. He discovered a shocking amount of paan stains, shabby paintwork and the lack of any funds towards its maintenance clearly showed. It’s largely the NRI visitors with a better sense of patriotism who take care of the place with their generosity and Raman, the last man standing, does his best to pay obeisance to it, despite the odds being entirely against him and his small family. It’s genuinely heartbreaking to see what we’ve made of the Syedna’s monumental gesture.

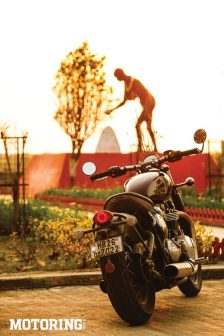

The Mini and Triumph, parked against a larger-than-life statue of Gandhi collecting salt from a mound, painted a poignant picture. These machines have their origins in a land that brought us together as a nation, even if through adversity. Being ruled by the British is surely not a pleasant memory for millions of Indians, but then what have we really achieved with a country our forefathers gave up their lives for? The British, for all their conquests, are a people respectful of their tradition, of what made them an industrious and visionary country. It’s why machines like the Mini and the Triumph even exist. Yes, it’s business at the end of the day, but even through it, you cannot deny the underlying hand of a deep reverential sense towards Britain’s history. What we can casually term ‘retro cool’ still has its roots in a sense of nationalistic pride. And us? What have we got to show for it? Lay’s wrappers, eh?

Would we have been better off if the British were still here? Most certainly not, but I wish they’d left us with a better sociological conditioning than that of mere rebellion and victory. The departure of the British fuelled our pride and our sovereignty but took away the last traces of ingenuity India was once renowned for. While ingenuity is a big ask, a sense of preservation, backed by a genuine (and not votebank-driven) sense of nationalism isn’t, right? It is for reasons more than simple impracticality that we don’t want the British back. Their machines, however, are a beautiful form of education, perhaps the best kind there can be. A history lesson involving a cool car and a cooler bike? Bet nobody will want to study in Poland, then.

[This story was originally published in our July 2017 issue]